Egyptologist Tweets Instructions on How to Topple an Obelisk; Protestors Use Them to Tear Down a Obelisk-Shaped Confederate Monument in Birmingham, Alabama

Almost three years ago, in Durham, North Carolina where I live, protestors pulled down a Confederate statue in front of the old courthouse after the fatal attacks at Charlottesville’s Unite the Right rally, an event itself ostensibly about protecting a Confederate statue. Now, the Sons of Confederate Veterans, who dedicated the Durham monument in 1924, want to see the statue go back up, in accordance with a 2015 state law prohibiting the removal of “historical monuments” by any local government without the express approval of the N.C. Historical Commission.

That law, of course, is why local residents could not get the statue removed legally, even though the city council would have done so in a heartbeat. Exasperated and faced with either the perpetual glorification of the slave-holding South on Main Street or with the breaking of an unjust law, they finally chose to fling a rope around the anonymous tin gray soldier and pull it to the ground. They didn’t have the easiest time getting it down. (Though it only took one person to topple Silent Sam, the Confederate soldier formerly on the University of North Carolina’s Chapel Hill campus.)

Hundreds of Confederate monuments around the U.S. were cheaply made and mass produced in the early 20th century, part of a coordinated campaign of symbolic terror to accompany a wave of lynchings and a Lost Cause whitewashing of history. Many of them are hollow, but the effigies can still put up a fight. Many more are also protected by state laws prohibiting their removal (7 states in all). Such is the case in Birmingham, Alabama. The state passed a law in 2017 banning local governments from removing or renaming monuments more than 40 years old, conveniently covering the period when all the Confederate statues, streets, schools, etc. went up.

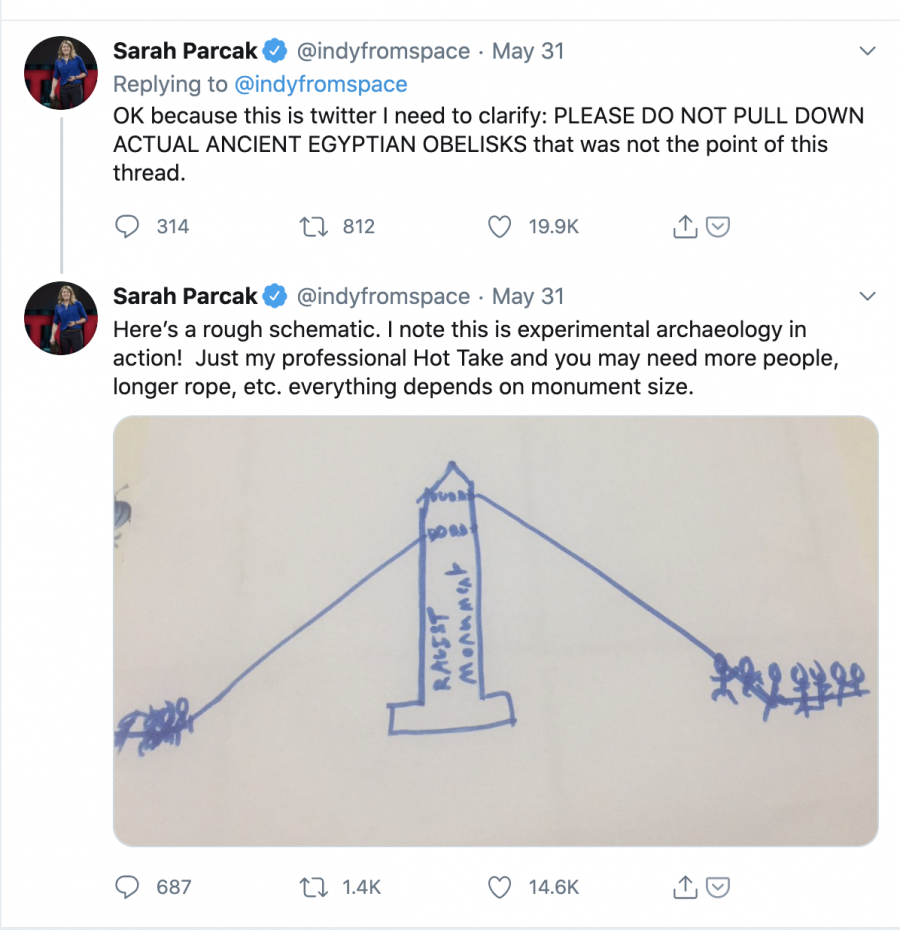

Wanting to help solve both of these problems—the physical resilience of certain monuments and the lack of legal remedies—Egyptologist Sarah Parcak suggested on Twitter some ancient math for taking down an obelisk that might make quick work of a Confederate monument, which also happened to be an obelisk. Her lengthy Twitter thread details the ratio of monument size to number of people needed to topple it, and recommends chains instead of ropes. She suggests “two groups, one on one side, one opposite,” pulling back and forth in a coordinated rhythm (driven by someone with a loudspeaker, ideally, and a song).

Parcak included a sketch and wrote slyly that sometimes an Egyptian obelisk can “masquerade as a racist monument,” wink, wink, nudge, nudge. “There might be just one like this in downtown Birmingham!” she concluded, “What a coincidence. Can someone please show this thread to the folks there.” Sure enough, there was such a monument, until the following evening, when “crowds protesting police brutality… tried to tear down the 52-foot-tall obelisk, known as the Confederate Soldiers and Sailors Monument, in Birmingham’s Linn Park,” notes Artnet news.

Despite Parcak’s precise instructions, her work of “experimental archaeology” may need tweaking. Protesters were unable to pull it down completely and the mayor stepped in and ordered a crew to finish the job. But people all over the U.S.—and in Bristol, U.K. and elsewhere—have been very successful ridding their cities of racist monuments to people who did everything in their power to perpetuate African slavery, colonial exploitation, and indigenous genocide while profiting handsomely. There are even maps showing people where to find such statues near them. May all such monuments to racism fall, may we learn why they went up in the first place, and may the people who lament their loss find better heroes.

via Artnet

Related Content:

An Anti-Racist Reading List: 20 Books Recommended by Open Culture Readers

The Civil War & Reconstruction: A Free Course from Yale University

How the “First Photojournalist,” Mathew Brady, Shocked the Nation with Photos from the Civil War

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Egyptologist Tweets Instructions on How to Topple an Obelisk; Protestors Use Them to Tear Down a Obelisk-Shaped Confederate Monument in Birmingham, Alabama is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2YmsqIB

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment