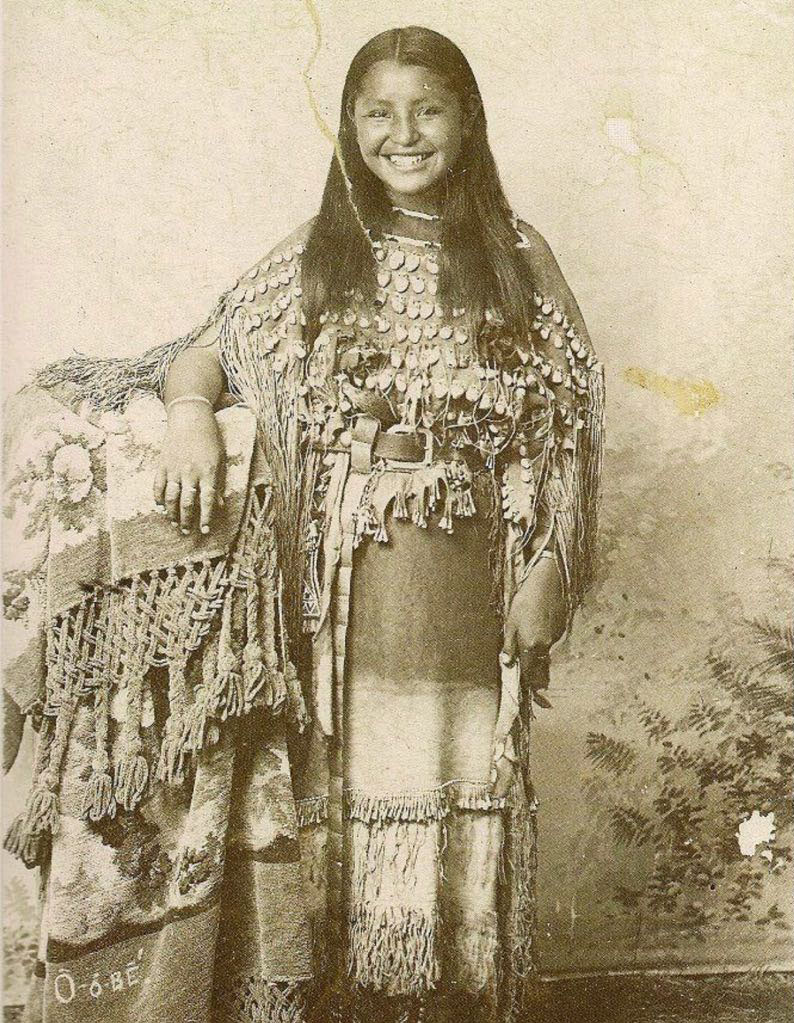

Just look at this photo. Just look at this young girl’s smile. We know her name: O-o-dee. And we know that she was a member of the Kiowa tribe in the Oklahoma Territory. And we know that the photo was taken in 1894. But that smile is like a time machine. O-o-dee might just as well have donned some traditional/historical garb, posed for her friends, and had them put on the ol’ sepia filter on her camera app.

But why? What is it about the smile?

For one thing, we are not used to seeing them in old photographs, especially ones from the 19th century. When photography was first invented, exposures could take 45 minutes. Having a portrait taken meant sitting stock still for a very long time, so smiling was right out. It was only near the end of the 19th century that shutter speeds improved, as did emulsions, meaning that spontaneous moments could be captured. Still, smiling was not part of many cultures. It could be seen as unseemly or undignified, and many people rarely sat for photos anyway. Photographs were seen by many people as a "passage to immortality" and seriousness was seen as less ephemeral.

Presidents didn’t officially smile until Franklin D. Roosevelt, which came at a time of great sorrow and uncertainty for a nation in the grips of the Great Depression. The president did it because Americans couldn’t.

Smiling seems so natural to us, it’s hard to think it hasn’t always been a part of art. One of the first thing babies learn is the power of a smile, and how it can melt hearts all around. So why hasn’t the smile been commonplace in art?

Historian Colin Jones wrote a whole book about this, called The Smile Revolution in Eighteenth Century Paris, starting with a 1787 self-portrait by Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun that depicted her and her infant. Unlike the coy half-smiles as seen in the Mona Lisa, Madame Le Brun’s painting showed the first white, toothy smile. Jones says it caused a scandal--smiles like this one were undignified. The only broad smiles seen in Renaissance painting were from children (who didn’t know better), the filthy plebiscite, or the insane. What had happened? Jones credits the change to two things: the emergence of dentistry over the previous hundred years (including the invention of the toothbrush), and the emergence of a “cult of sensibility and politeness.” Jones explains this by looking at the heroines of the 18th century novel, where a smile meant an open heart, and not a sarcastic smirk:

Now, O-o-dee and Jane Austen’s Emma might have been worlds apart, but so are we--creatures of technology, smiling at our iPhones as we take another selfie--from that Kiowan girl in the Fort Sill, Oklahoma studio of George W. Bretz.

via PetaPixel

Related Content:

Visit a New Digital Archive of 2.2 Million Images from the First Hundred Years of Photography

Take a Visual Journey Through 181 Years of Street Photography (1838-2019)

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the Notes from the Shed podcast and is the producer of KCRW's Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, and/or watch his films here.

A Rare Smile Captured in a 19th Century Photograph is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2Ymfd2A

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment