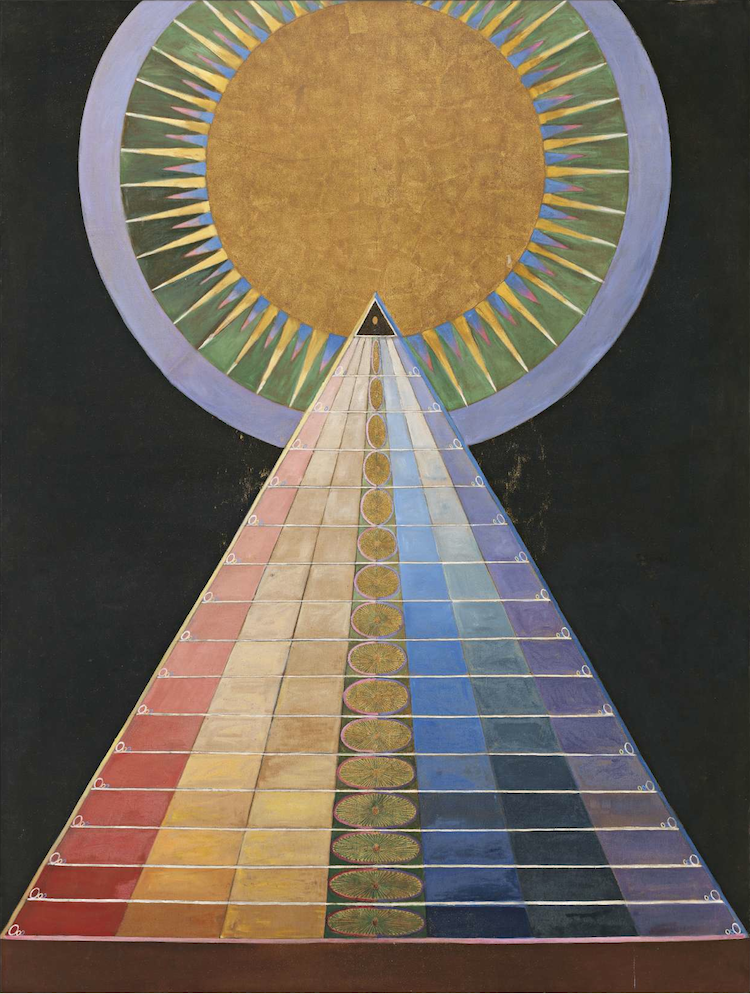

It's not often an entire chapter of art history textbooks needs rewriting, but as fans of Hilma af Klint see it, one such time has come. A Swedish artist and mystic who lived from the mid-19th to the mid-20th century, af Klint left behind a body of work amounting to more than 1,200 paintings — all of which she insisted not be taken out of storage until 20 years after her death. She suspected the public wouldn't be ready for them before then, and she was more right than she knew: offered the paintings as a donation in the 1970s, Stockholm's Moderna Museet turned them down. Only in the following decade did the art history world begin to understand that, far from just a productive amateur painting in obscurity, af Kint might be the very first abstract artist.

Today af Klint's abstract paintings, the first of which she produced in middle-age in 1906, have appreciators all over the world. Some, we'd like to think, came because of all the times we've previously featured her here on Open Culture; others were brought in by the Guggenheim's recent retrospective Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future.

These paintings, says the museum's web site, "were like little that had been seen before: bold, colorful, and untethered from any recognizable references to the physical world. It was years before Vasily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich, Piet Mondrian, and others would take similar strides to rid their own artwork of representational content." This year the story of af Klint and her work is told cinematically in Beyond the Visible, a new documentary by German filmmaker Halina Dyrschka whose trailer appears at the top of the post.

In his review of the film, New York Times critic A.O. Scott briefly recounts af Klint's early years: "Born in 1862 to an aristocratic Swedish family and raised partly on the grounds of the military academy where her father was an instructor, she trained at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm, mastering the traditional genres of portrait, still life and landscape. By the late 1880s, her notebooks and paintings began incorporating forms that, while they sometimes evoked natural phenomena (like snail shells, flower petals and insect wings), did not resemble anything in the visible world." This change in the artist's aesthetic sensibility came along with her growing interest in mysticism and ways of accessing a realm beyond human senses. (She even offered a painting to the Anthroposophical Society founder Rudolf Steiner, who rejected it.)

Scott calls Beyond the Visible "a chapter in the wholesale revision of the critical and historical record that began only recently, and it enlists a passionate and knowledgeable cadre of curators, scholars, scientists and artists to press the argument for af Klint’s importance." But "the paintings themselves are the best evidence — even through the mediation of a home screen, their vibrancy, wit and formal command is thrilling." With many movie theaters temporarily shut down by the coronavirus epidemic, you can watch the documentary through Kino Marquee's "virtual cinema," a service that streams over the internet but also supports local art houses. Most of us may be no closer to the unseen world into which af Klint yearned to tap than were any of her everyday compatriots. But as far as historical moments in which her work and life can find a fascinated audience, there's never been a better one.

Related Content:

Discover Hilma af Klint: Pioneering Mystical Painter and Perhaps the First Abstract Artist

Who Painted the First Abstract Painting?: Wassily Kandinsky? Hilma af Klint? Or Another Contender?

Steve Martin on How to Look at Abstract Art

An Interactive Social Network of Abstract Artists: Kandinsky, Picasso, Brancusi & Many More

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

New Hilma af Klint Documentary Explores the Life & Art of the Trailblazing Abstract Artist is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2Krp3cW

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment