There is a level of avarice and depravity in defrauding victims of an epidemic that should shock even the most jaded. But a look into the archives of history confirms that venal mountebanks and con artists have always followed disaster when it strikes. In 1665, the Black Death reappeared in London, a disease that had ravaged medieval Europe for centuries and left an indelible impression on cultural memory. After the rats began to spread disease, terror spread with it. Then came the advertisements for sure cures.

“Everyone dreaded catching the disease,” notes the British Library. “Victims were often nailed into their houses in an attempt to stop the spread… They usually died within days, in agony and madness from fevers and infected swellings.” This grotesque scene of panic and pain seemed like a growth market to “quack doctors selling fake remedies. There were many different pills and potions,” and they “were often very expensive to buy and claimed, falsely, to have been successfully used in previous epidemics.”

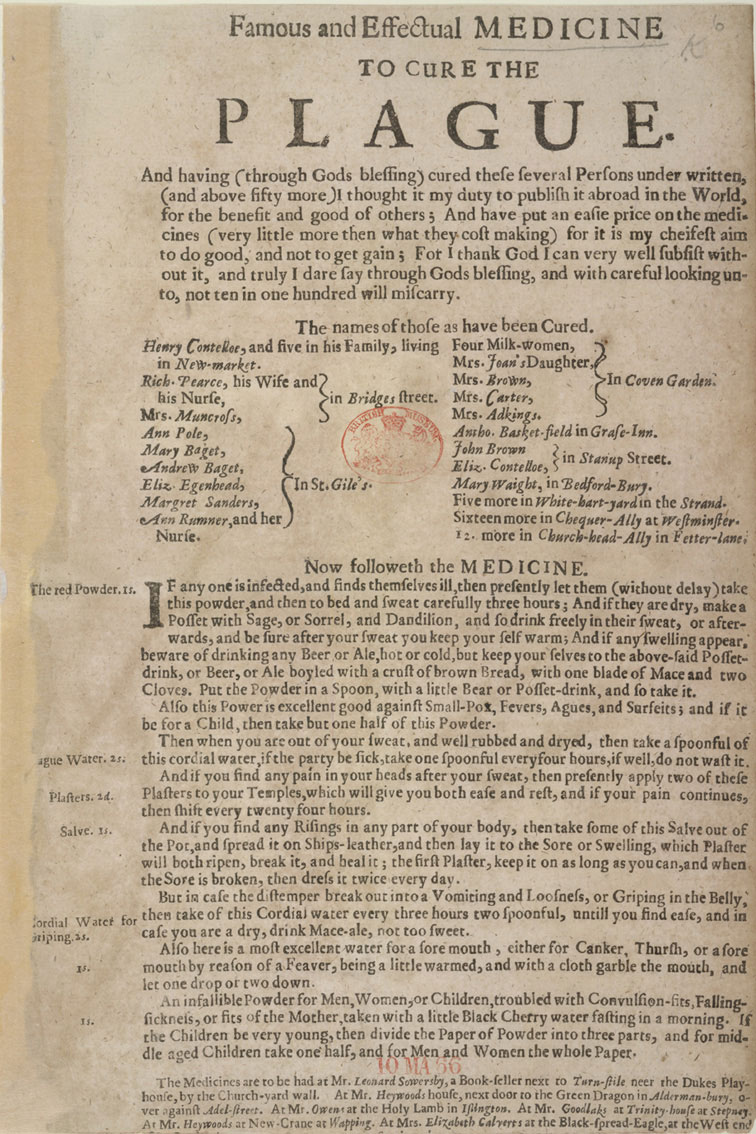

Surely, there were many in the medical profession, such as it was, who genuinely wanted to help, but no honest doctor could claim, as the broadside above does, to have discovered a “Famous and Effectual MEDICINE TO CURE THE PLAGUE.” So confident is this ad that it lists the names and locations of several people supposedly cured (and promises to have cured “above fifty more”). You can go look up “Andrew Baget, in St. Gile’s,” or “Mrs. Adkings. In Coven Garden,” or “Mary-Waight, in Bedford-Bury.” Ask them yourself! Only, that might be a little difficult as you’ve currently got the plague…. (See a transcription of the advertisement here.)

This particular example appears to have been a guild effort. At the bottom of the pamphlet we find a list of merchants offering the needed ingredients for the medicine, which sufferers would presumably mix themselves, having first visited the shops of Mr. Leonard Sowersby, Mr. Heywoods, Mr. Owens, Mr. Goodlaks, a second Mr. Heywoods, and Mrs. Elizabeth Calverts (potentially infecting others all the time.) Customers were clearly desperate. They aren’t even given the stamp of a physician’s approval, only the merchants' promise that others have returned from the brink by means of an “infallible Powder” that also cures “Small-Pox, Fevers, Agues, and Surfeits.” Children should take half a dose.

17th century physicians fared little better against the plague than doctors had over 300 years earlier when the disease first made its appearance in Europe in 1347, traveling from Asia to Italy. They did what they could, as the BBC points out, recommending “mustard, mint sauce, apple sauce and horseradish” as dietary aids. Other attempted 14th century cures included “rubbing onions, herbs or a chopped up snake (if available) on the boils or cutting up a pigeon and rubbing it over an infected body.”

This sounded specious to many people at the time. One 1380 source, Jean Froissart’s Chronicles, stated sarcastically, “doctors need three qualifications: to be able to lie and not get caught; to pretend to be honest; and to cause death without guilt.” Such qualifications have always suited those intent on careers in government or finance, where times of trouble can be highly profitable. We are fortunate, however, for the advances of modern medicine, and for medical professionals who risk their lives daily for victims of COVID-19, even if some other human qualities haven’t changed since people tried to end pandemics by marching through the streets whipping themselves.

Related Content:

The History of the Plague: Every Major Epidemic in an Animated Map

Download Classic Works of Plague Fiction: From Daniel Defoe & Mary Shelley, to Edgar Allan Poe

Why You Should Read The Plague, the Albert Camus Novel the Coronavirus Has Made a Bestseller Again

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

A 1665 Advertisement Promises a “Famous and Effectual” Cure for the Great Plague is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2y0RueH

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment