Did a Scottish Poet Invent the F-Word? A 1568 Anthology Compiled Under Plague Quarantine Suggests So

"Wan fukkit funling": as an insult, these words would today land a minor blow at most. Not so in Scotland of the early 16th century, in which William Dunbar and Walter Kennedy, two of the land's well-known poets, faced off before the court of King James IV in a contest of rhyme. The event is memorialized in the poem "The Flyting of Dunbar and Kennedie," one of 400 anthologized in what's known as the Bannatyne Manuscript. Compiled in 1568 by an Edinburgh merchant named George Bannatyne, stuck at home while a plague swept his city — a condition many can relate to these days — it now enjoys pride of place at the National Library of Scotland as a cultural treasure, not least because it contains what may be the oldest recorded use of the F-word.

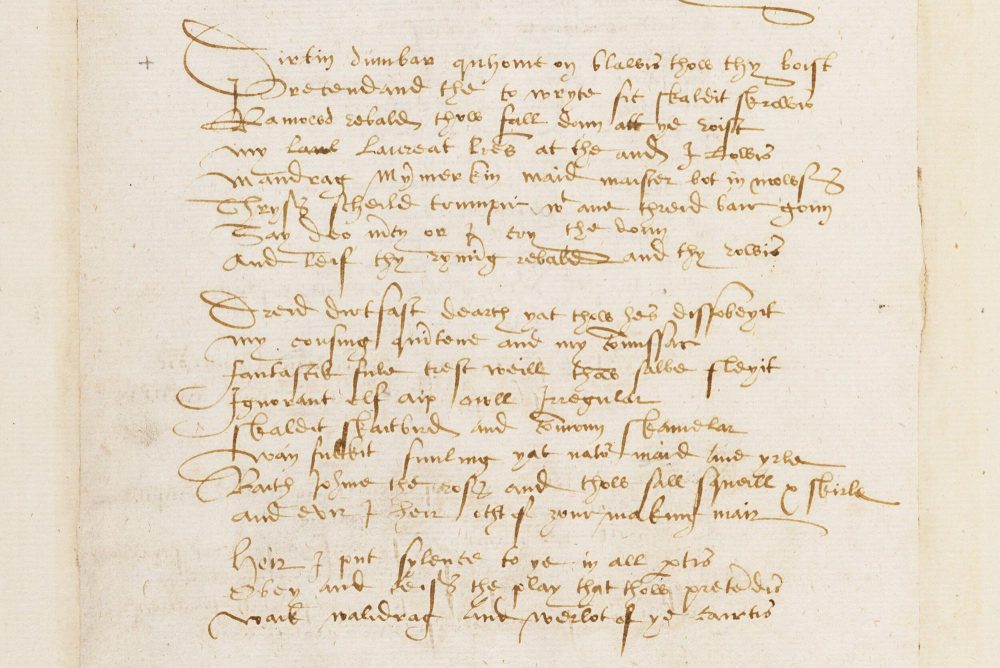

The Bannatyne Manuscript and "wan fukkit funling" (whose appearance you can see in the image at the top of the post, in the sixth line from the bottom) play an important part in the new BBC Scotland documentary Scotland – Contains Strong Language. The hour-long program, writes The Scotsman's Brian Ferguson, "sees actress, singer and theatre-maker Cora Bissett trace the nation’s long love affair with swearing and insults, despite the long-standing efforts of religious leaders to condemn it as a sin." Ferguson quotes Bissett describing the importance of this particular "flyting" ("the 16th century equivalent of a rap battle") as follows: "When Kennedy addresses Dunbar, there is the earliest surviving record of the word ‘f***’ in the world."

"In the poem, Dunbar makes fun of Kennedy's Highland dialect, for instance, as well as his personal appearance, and he suggests his opponent enjoys sexual intercourse with horses," writes Ars Technica's Jennifer Ouellette. "Kennedy retaliates with attacks on Dunbar's diminutive stature and lack of bowel control, suggesting his rival gets his inspiration from drinking 'frogspawn' from the waters of a rural pond." All highly amusing, to be sure, but given how few of us English-speakers will immediately recognize in "wan fukkit funling" the curse with which we've grown so intimately familiar, does this really count as an example of usage in English?

'To me, that looks more like Scots than Middle English," writes Boing Boing's Thom Dunn, "although both languages were derived from Olde English." (He also reminds us not to confuse Scots with the separate language of Scottish Gaelic.) Medieval historian Kristin Uscinski writes in to Ars Technica to point out a certain "Roger F$#%-by-the-Navel who appears in some court records from 1310-11" — previously featured, of course, here on Open Culture. Historians and linguists will surely continue doing their own kind of battle to determine what counts as the first true F-word, making more discoveries about the English language's heritage of swearing along the way. One thing is certain: if any nation has made a rich use of that heritage, it's Scotland.

Related Content:

The Earliest Known Appearance of the F-Word, in a Bizarre Court Record Entry from 1310

The Very First Written Use of the F Word in English (1528)

Steven Pinker Explains the Neuroscience of Swearing (NSFW)

Stephen Fry, Language Enthusiast, Defends The “Unnecessary” Art Of Swearing

A Lecture About the History of the Scots Language … in Scots: How Much Can You Comprehend?

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Did a Scottish Poet Invent the F-Word? A 1568 Anthology Compiled Under Plague Quarantine Suggests So is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2yJbKlC

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment