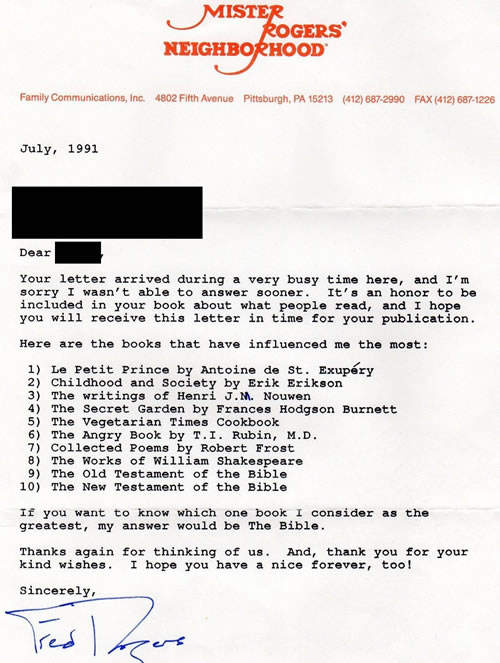

In 1991, Fred Rogers received a letter from an author working on a book about others' favorite books. More than likely, it was a book about famous people's favorite books. But you wouldn’t know it from Mister Rogers’ characteristically gracious typed reply, above. He opens by apologizing for his late reply and expresses his honor at being included in a “book about what people read.” What did the most unassuming and neighborly person on television read?

You can see Rogers’ list of ten books transcribed below, though his final two choices, the Old and New Testaments, might count as either one book or a collection of many, depending on one's views. Roger’s himself was very clear about his beliefs when he wasn't onscreen, The ordained Presbyterian minister concludes by adding, “If you want to know which one book I consider as the greatest, my answer would be The Bible.”

Rogers didn’t give anyone who knew him reason to doubt his sincerity. What becomes evident in both a recent biography, The Good Neighbor, and Morgan Neville’s documentary film, Won’t You Be My Neighbor, is that he "was exactly what he appeared to be,” as Anya Kamenetz writes at NPR. “Someone who devoted his life to taking seriously and responding to the emotions of children. In a word: to love.”

- Le Petit Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

- Childhood and Society by Erik Erikson

- The Writings of Henri J.M. Nouwen

- The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett

- The Vegetarian Times Cookbook

- The Angry Book by T.I. Rubin, M.D.

- Collected Poems of Robert Frost

- The Works of William Shakespeare

- The Old Testament of the Bible

- The New Testament of the Bible

The way he expressed that love, however, was quite unusual in both religious and secular circles. He was, Heidi Ledford writer at Nature, “neither zany entertainer nor earnest pedagogue. Rogers was instead a respectful mentor who promoted tolerance.” He considered the show his God-given mission, but “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood was religion-free.” Rogers never preached, and never excluded anyone from his neighborhood.

Another reason his slow, repetitive show had such wide and enduring appeal was that Rogers crafted each episode to meet preschoolers’ psychosocial needs, in frequent consultation with his mentor of 30 years, child psychologist Margaret McFarland. Rogers was well read on the subject and understood its critical importance to early childhood education to kids' emotional and intellectual development. His ideas “are as relevant as ever,” writes Kamenetz.

Those ideas include the centrality of imaginative play in early childhood, which Rogers offered to many children who didn't get much opportunity to explore their creativity. His religious faith may have grounded his lifelong commitment to making all kids feel valued and understood, yet it's hard not to notice that he lists the two parts of The Bible last on his list.

His first choice is one of the most imaginative books ever written for children—one that doesn’t talk down to them and treats their emotions with serious, yet playful, respect, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s Le Petit Prince. He follows up this classic with Childhood and Society, Erik Erikson's post-Freudian exploration of child development.

On the whole, Rogers’ reading list, just like his show, offers a portrait of a one-of-a-kind figure: a children’s entertainer with an educational style that drew substance from the best literature, social science, and psychology of its time, while taking its charitable spirit from Rogers’ own personal belief in universal love as the most important educational methodology.

Related Content:

Mr. Rogers’ Nine Rules for Speaking to Children (1977)

The First & Last Time Mister Rogers Sang “Won’t You Be My Neighbor” (1968-2001)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.

Mister Rogers Makes a List of His 10 Favorite Books is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3ansex6

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment