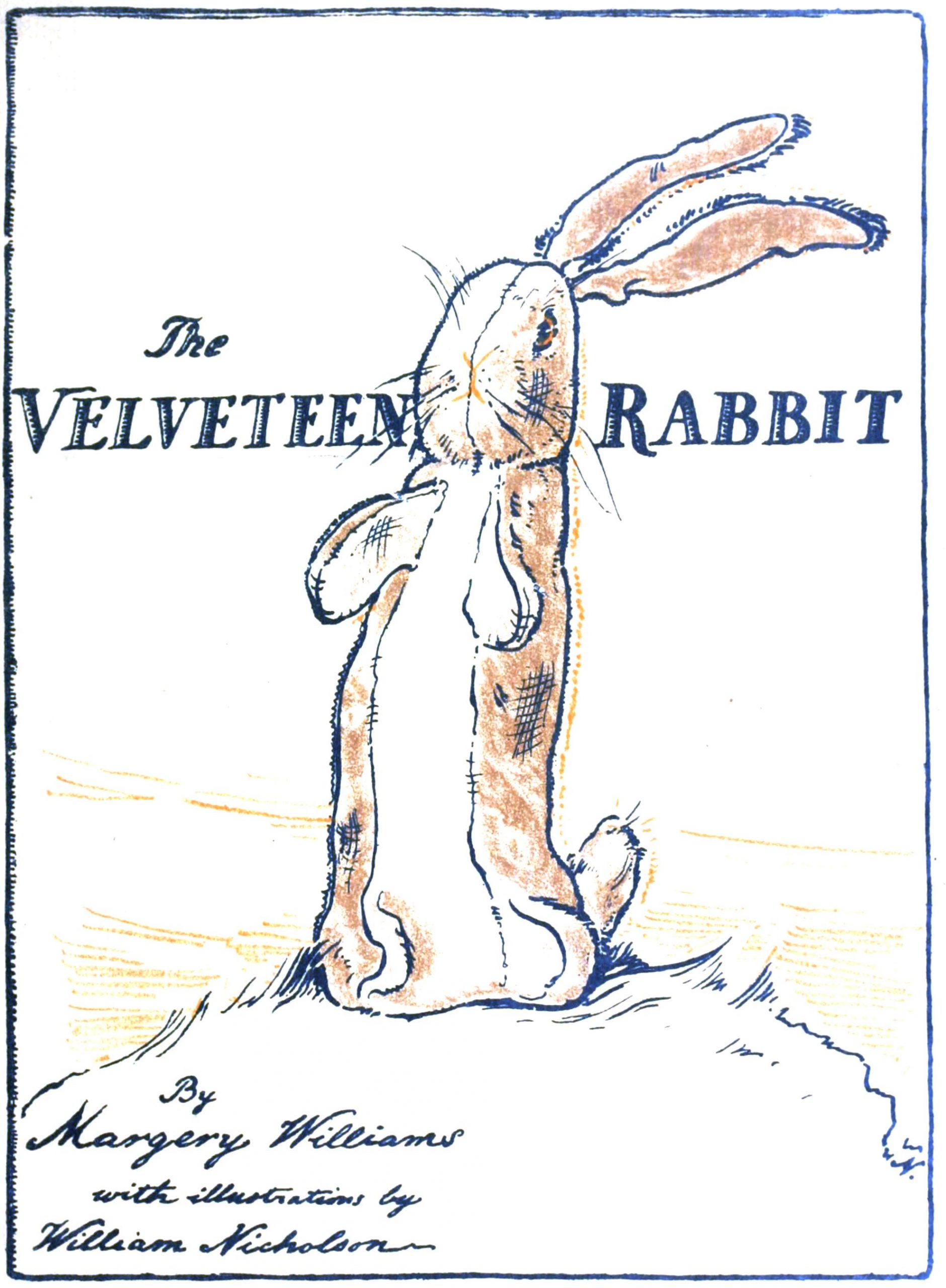

It is no arbitrary coincidence that Margery Williams’ classic The Velveteen Rabbit involves a terrifying brush with scarlet fever. Published in 1922, the book was based on her own children. But all of its first readers would have shuddered at the mention, given very recent memories of the global devastation wrought by “Spanish” flu. The story earns its fairy-tale ending by invoking catastrophe, with images of the poor rabbit nearly thrown into the fire and then tossed out with the trash.

The Velveteen Rabbit recalls Oscar Wilde’s 19th century children’s stories, in which “loss is not a pose; it is real,” writes Jeanette Winterson. All may eventually be restored, "there is usually a happy ending,” but “Wilde’s fairytale transformations turn on loss.” The author of The Velveteen Rabbit did not share Wilde's contrarian streak, nor indulge the same sentimental fits of piety, but Williams’ intent was no less profound and serious. The specter of fever still haunts the book's Arcadian ending.

Williams' major influence was Walter de la Mare, whom the Poetry Foundation describes as a writer of “dreams, death, rare states of mind and emotion, fantasy worlds of childhood, and the pursuit of the transcendent”—all themes The Velveteen Rabbit engages in the narrative language of kids. Do children's books still recognize early childhood as uniquely formative, while also regarding children as sophisticated readers who can appreciate emotional depth and psychological complexity?

Do Disney’s modern franchises take loss as seriously? What about Paw Patrol? Were Wilde and Williams’ stories unusual for their time or did they mark a trend? How do children’s books serve as codes of conduct, and what do they tell us about how we filter life’s calamities in digestible narratives for our kids? How can we use such stories to educate in the midst of overwhelming events?

For those who find these questions intriguing for purely academic reasons, or who struggle with them as both parents and newly minted homeschool teachers, we offer, below, several online libraries with thousands of scanned historical children’s books, from very early printed examples in the 18th century to examples of a much more recent vintage.

These come from publishers in England, the U.S., and the Soviet Union, and from names like Christina Rosetti, Jules Verne, Wizard of Oz author Frank L. Baum, and English artist Randolph Caldecott, whose surname has distinguished the best American picture books for 70 years. For every star of children’s writing and illustration, there are hundreds of writers and artists hardly anyone remembers, but whose work can be as playful, moving, and honest as the famous classic children’s stories we pass on to our kids.

Marvel at the Library of Congress’s small but significant online collection of books from the 19th and 20th centuries

And, finally, at Princeton's online collections, browse Soviet children’s books published between 1917 and 1953, for a very different view of early childhood education.

Whether we're parents, scholars, teachers, curious readers, or all of the above, we find that the best children’s books show us “why we need fairy tales,” as Winterson writes, at every age. “Reason and logic are tools for understanding the world. We need a means of understanding ourselves, too. That is what imagination allows.”

Related Content:

Hayao Miyazaki Picks His 50 Favorite Children’s Books

200 Free Kids Educational Resources: Video Lessons, Apps, Books, Websites & More

Watch Stars Read Classic Children’s Books: Betty White, James Earl Jones, Rita Moreno & Many More

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Digital Archives Give You Free Access Thousands of Historical Children’s Books is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2WyokxY

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment