When I order a cup of tea in Korea, where I live, I ask for cha (?); when traveling in Japan, I ask for the honorific-affixed ocha (??). In Spanish-speaking places I order té, which I try to pronounce as distinctly as possible from the thé I order in French-speaking ones. And on my trips back to United States, where I'm from, I just ask for tea. Not that tea, despite its awe-inspiring venerability, has ever quite matched the popularity of coffee in America, but you can still find it most everywhere you go. And for decades now, no less an American corporate coffee juggernaut than Starbucks has labeled certain of its teas chai, which has popularized that alternative term but also created a degree of public confusion: what's the difference, if any, between chai and tea?

Both words refer, ultimately, to the same beverage invented in China more than three millennia ago. Tea may now be drunk all over the world, but people in different places prefer different kinds: flavors vary from region to region within China, and Chinese teas taste different from, say, Indian teas. Starbucks presumably brands its Indian-style tea with the word chai because it sounds like the words used to refer to tea in India.

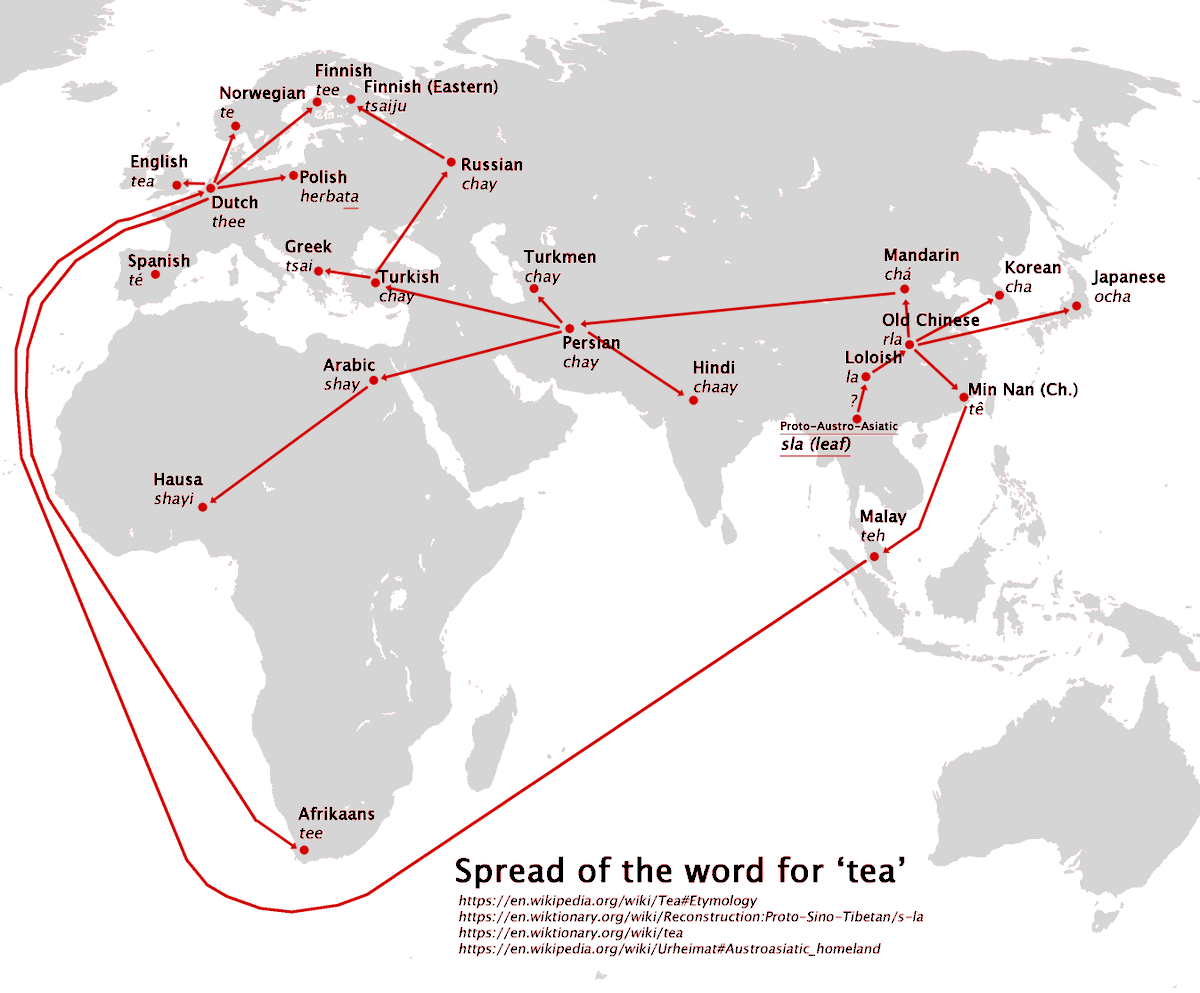

It also sounds like the words used to refer to tea in Farsi, Turkish, and even Russian, all of them similar to chay. But other countries' words for tea sound different: the Maylay teh, the Finnish tee, the Dutch thee. "The words that sound like 'cha' spread across land, along the Silk Road," writes Quartz's Nikhil Sonnad. "The 'tea'-like phrasings spread over water, by Dutch traders bringing the novel leaves back to Europe."

"The term cha (?) is 'Sinitic,' meaning it is common to many varieties of Chinese," writes Sonnad. "It began in China and made its way through central Asia, eventually becoming 'chay' (???) in Persian. That is no doubt due to the trade routes of the Silk Road, along which, according to a recent discovery, tea was traded over 2,000 years ago." The te form "used in coastal-Chinese languages spread to Europe via the Dutch, who became the primary traders of tea between Europe and Asia in the 17th century, as explained in the World Atlas of Language Structures. The main Dutch ports in east Asia were in Fujian and Taiwan, both places where people used the te pronunciation. The Dutch East India Company’s expansive tea importation into Europe gave us the French thé, the German Tee, and the English tea."

And we mustn't leave out the Portuguese, who in the 1500s "travelled to the Far East hoping to gain a monopoly on the spice trade," as Culture Trip's Rachel Deason writes, but "decided to focus on exporting tea instead. The Portuguese called the drink cha, just like the people of southern China did," and under that name shipped its leaves "down through Indonesia, under the southern tip of Africa, and back up to western Europe." You can see the global spread of tea, tee, thé, chai, chay, cha, or whatever you call it in the map above, recently tweeted out by East Asia historian Nick Kapur. (You may remember the fantastical Japanese history of America he sent into circulation last year.) Study it carefully, and you'll be able to order tea in the lands of both te and cha. But should you find yourself in Burma, it won't help you: just remember that the word there is lakphak.

Related Content:

1934 Map Resizes the World to Show Which Country Drinks the Most Tea

10 Golden Rules for Making the Perfect Cup of Tea (1941)

George Orwell’s Rules for Making the Perfect Cup of Tea: A Short Animation

Epic Tea Time with Alan Rickman

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

A Map of How the Word “Tea” Spread Across the World is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/32rrkLN

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment