Jane Austen read voraciously and as widely as she could in her circumscribed life. Even so, she told her niece Caroline, she wished she had “read more and written less” in her formative years. Her nephew James Edward Austen-Leigh made clear that no matter how much she read, her work was far more than the sum of her reading: “It was not,” he wrote in his 1870 biography, “what she knew, but what she was, that distinguished her from others.” What she was not, however, was the owner of a great library.

Members of Austen’s family were well-off, but she herself lived on modest means and never made enough from writing to become financially independent. She owned books, of course, but not many. Books were expensive, and most people borrowed them from lending libraries. Nonetheless, scholars have been able to piece together an extensive list of books Austen supposedly read—books mentioned in her letters, novels, and an 1817 biographical note written by her brother Henry in her posthumously published Northanger Abbey.

Austen read contemporary male and female novelists. She read histories, the poetry of Milton, Wordsworth, Byron, Cowper, and Sir Walter Scott, and novels written by family members. She read Chaucer, Locke, Rousseau, Hume, Spencer, and Wollstonecraft. She read ancients and modern. “Despite her desire to have ‘read more” in her youth,” write Austen scholars Gillian Down and Katie Halsey, “recent scholarship has established that the range of Austen’s reading was far wider and deeper than either Henry or James Edward suggest.”

Austen may not have had a large library of her own, but she did have access to the handsome collection at Godmersham Park, the home of her brother Edward Austen Knight. “For a total of ten months spread over fifteen years,” Rebecca Rego Barry writes at Lapham’s Quarterly, “Austen visited her brother at his Kent estate. The brimming bookshelves at Godmersham Park were a particular draw for the novelist.” In the last eight years of her life, Jane lived with her mother and sister Cassandra at Edward’s Chawton estate, in a villa that had its own library.

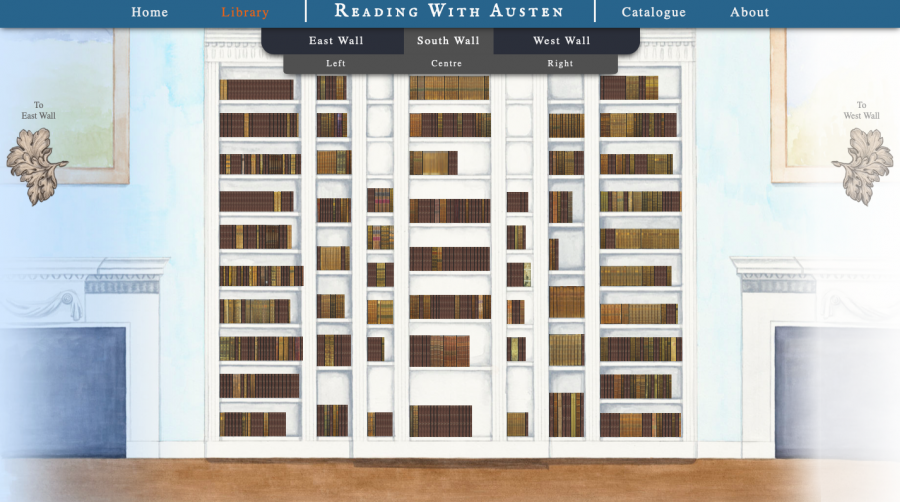

Reconstructing these shelves show us the books Austen would have regularly had in view, though scholars must use other evidence to show which books she read. In 2009, Down and Halsey curated an exhibition focused on her reading at Chawton. Ten years later, we can see the library at Godmersham Park recreated in a virtual version made jointly by Chawton House and McGill University’s Burney Center.

Called “Reading with Austen,” the interactive site lets us to navigate three book-lined walls of the library. “Users can hover over the shelves and click on any of the antique books,” writes Barry, “summoning bibliographic data and available photos of pertinent title pages, bookplates, and marginalia. Digging deeper, one can peruse a digital copy of the book and determine the whereabouts of the original.”

These volumes are what we might expect from an English country gentleman: books of law and agriculture, historical registers, travelogues, political theory, and classical Latin. There is also Shakespeare, Swift, and Voltaire, Austen’s own novels, and some of the contemporary fiction she particularly loved. The Burney Center “tried,” says director Peter Sabor, “to imagine Jane Austen actually walking around the library…. We’re basically looking over her shoulder as she looks at the bookshelf.” It’s not exactly quite like that at all, but the project can give us a sense of how much Austen treasured libraries.

She wrote about libraries as a sign of luxury. In an early unfinished novel, "Catherine," she has a furious character exclaim in reproach, "I gave you the key to my own Library, and borrowed a great many good books of my Neighbors for you." Austen may have feared losing library and lending access, and she longed for a kingdom of books all her own. During her final visit to Godmersham Park in 1813, she wrote to her sister, “I am now alone in the Library, Mistress of all I survey.”

Try to imagine how she might have felt as you peruse the library’s haphazardly arranged contents. Consider which of these books she might have read and which she might have shelved and why. Enter the "Reading with Austen" library project here.

Related Content:

Download the Major Works of Jane Austen as Free eBooks & Audio Books

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Take a Virtual Tour of Jane Austen’s Library is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2yRHku3

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment