Is perpetual motion possible? In theory… I have no idea…. In practice, so far at least, the answer has been a perpetual no. As Nicholas Barrial writes at Makery, “in order to succeed,” a perpetual motion machine “should be free of friction, run in a vacuum chamber and be totally silent” since “sound equates to energy loss.” Trying to satisfy these conditions in a noisy, entropic physical world may seem like a fool’s errand, akin to turning base metals to gold. Yet the hundreds of scientists and engineers who have tried have been anything but fools.

The long list of contenders includes famed 12th-century Indian mathematician Bh?skara II, also-famed 17th-century Irish scientist Robert Boyle, and a certain Italian artist and inventor who needs no introduction. It will come as no surprise to learn that Leonardo da Vinci turned his hand to solving the puzzle of perpetual motion. But it seems, in doing so, he “may have been a dirty, rotten hypocrite,” Ross Pomery jokes at Real Clear Science. Surveying the many failed attempts to make a machine that ran forever, he publicly exclaimed, “Oh, ye seekers after perpetual motion, how many vain chimeras have you pursued? Go and take your place with the alchemists.”

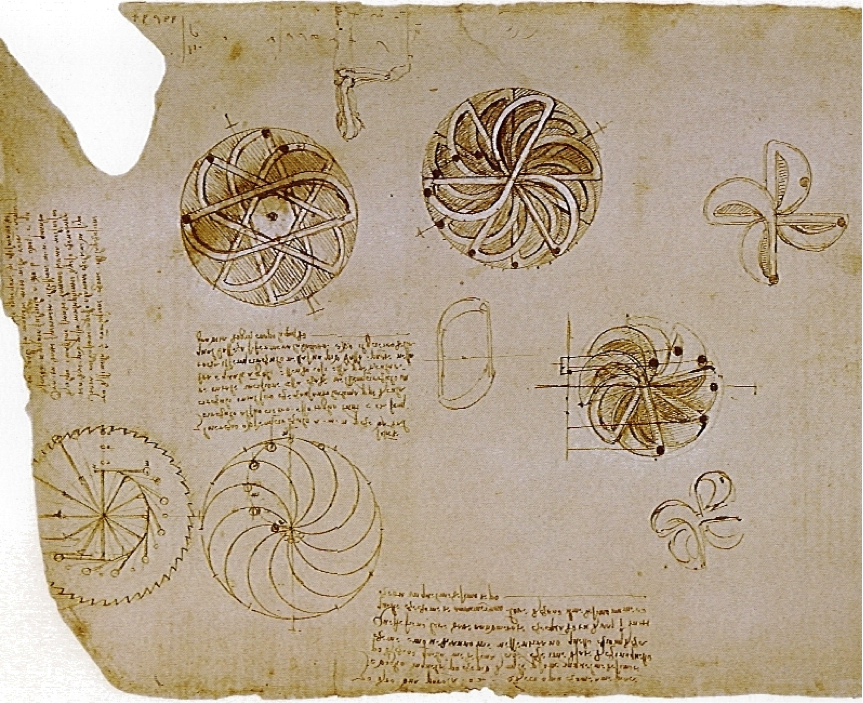

In private, however, as Michio Kaku writes in Physics of the Impossible, Leonardo “made ingenious sketches in his notebooks of self-propelling perpetual motion machines, including a centrifugal pump and a chimney jack used to turn a roasting skewer over a fire.” He also drew up plans for a wheel that would theoretically run forever. (Leonardo claimed he tried only to prove it couldn’t be done.) Inspired by a device invented by a contemporary Italian polymath named Mariano di Jacopo, known as Taccola (“the jackdaw"), the artist-engineer refined this previous attempt in his own elegant design.

Leonardo drew several variants of the wheel in his notebooks. Despite the fact that the wheel didn’t work—and that he apparently never thought it would—the design has become, Barrial notes, “THE most popular perpetual motion machine on DIY and 3D printing sites.” (One maker charmingly comments, in frustration, “Perpetual motion doesn’t seem to work, what am I doing wrong?”) The gif at the top, from the British Library, animates one of Leonardo’s many versions of unbalanced wheels. This detailed study can be found in folio 44v of the Codex Arundel, one of several collections of Leonardo’s notebooks that have been digitized and made publicly available online.

In his book The Innovators Behind Leonardo, Plinio Innocenzi describes these devices, consisting of "12 half-moon-shaped adjacent channels which allow the free movement of 12 small balls as a function of the wheel’s rotation…. At one point during the rotation, an imbalance will be created whereby more balls will find themselves on one side than the other,” creating a force that continues to propel the wheel forward indefinitely. “Leonardo reprimanded that despite the fact that everything might seem to work, ‘you will find the impossibility of motion above believed.’”

Leonardo also sketched and described a perpetual motion device using fluid mechanics, inventing the “self-filling flask” over two-hundred years before Robert Boyle tried to make perpetual motion with this method. This design also didn’t work. In reality, there are too many physical forces working against the dream of perpetual motion. Few of the attempts, however, have appeared in as elegant a form as Leonardo’s. See the fully scanned Codex Arundel at the British Library.

Related Content:

Leonardo da Vinci’s Visionary Notebooks Now Online: Browse 570 Digitized Pages

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leonardo da Vinci’s Elegant Design for a Perpetual Motion Machine is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2YOm47T

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment