NASA Enlists Andy Warhol, Annie Leibovitz, Norman Rockwell & 350 Other Artists to Visually Document America’s Space Program

It’s hard to imagine that the space-crazed general public needed any help getting worked up about astronauts and NASA in the early 60s.

Perhaps the wild popularity of space-related imagery is in part what motivated NASA administrator James Webb to create the NASA Art Program in 1962.

Although the program's handpicked artists weren’t edited or censored in any way, they were briefed on how NASA hoped to be represented, and the emotions their creations were meant capture—the excitement and uncertainty of exploring these frontiers.

NASA was also careful to collect everything the artists produced while participating in the program, from sketches to finished work.

In turn, they received unprecedented access to launch sites, key personnel, and major events such as Project Mercury and the Apollo 11 Mission.

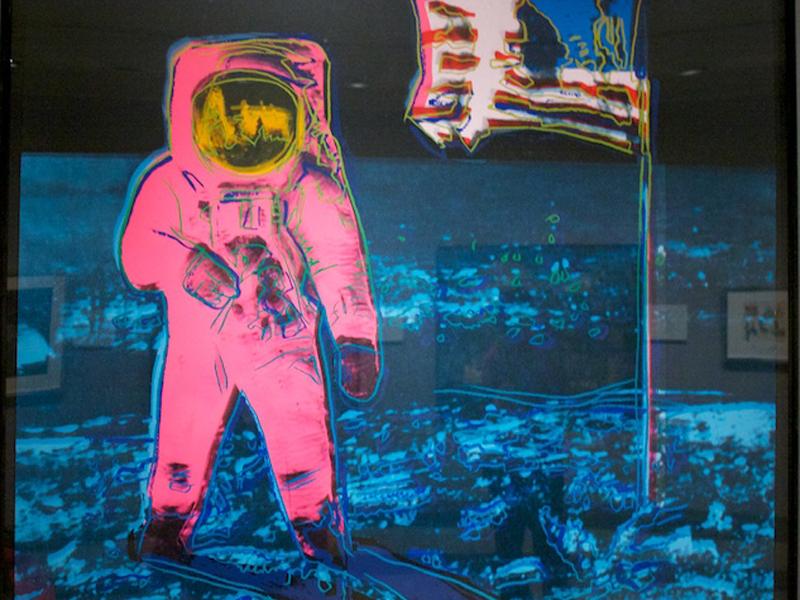

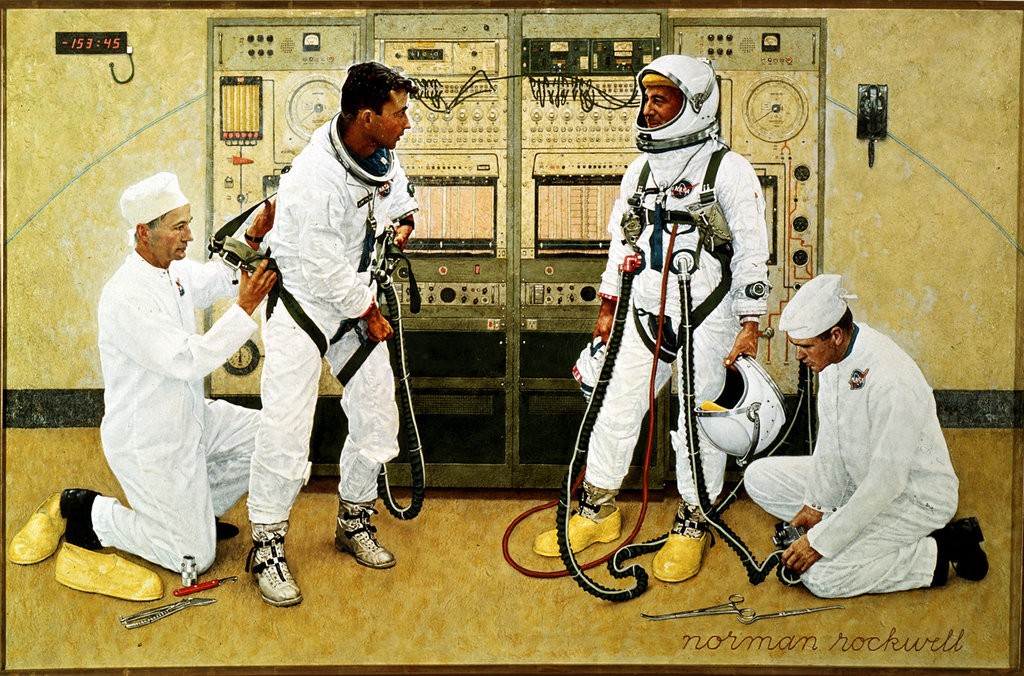

Over 350 artists, including Andy Warhol, Norman Rockwell, and Laurie Anderson, have brought their unique sensibilities to the project. (Find NASA-inspired art by Warhol and Rockwell above.)

(And hey, no shame if you mistakenly assumed Warhol’s 1987 Moonwalk 1 was created as a promo for MTV…)

Jamie Wyeth’s 1964 watercolor Gemini Launch Pad includes a humble bicycle, the means by which technicians traveled back and forth from the launch pad to the concrete-reinforced blockhouse where they worked.

Photographer Annie Leibovitz offers two views of NASA’s first female pilot and commander, Eileen Collins—with and without helmet.

Postage stamp designer, Paul Calle, one of the inaugural group of participating artists, produced a stamp commemorating the Gemini 4 space capsule in celebration of NASA's 9th anniversary. When the Apollo 11 astronauts suited up prior to blast off on July 16, 1969, Calle was the only artist present. His quickly rendered felt tip marker sketches lend a backstage element to the heroic iconography surrounding astronauts Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins. One of the items they carried with them on their journey was the engraved printing plate of Calle’s 1967 commemorative stamp. They hand-canceled a proof aboard the flight, on the assumption that post offices might be hard to come by on the moon.

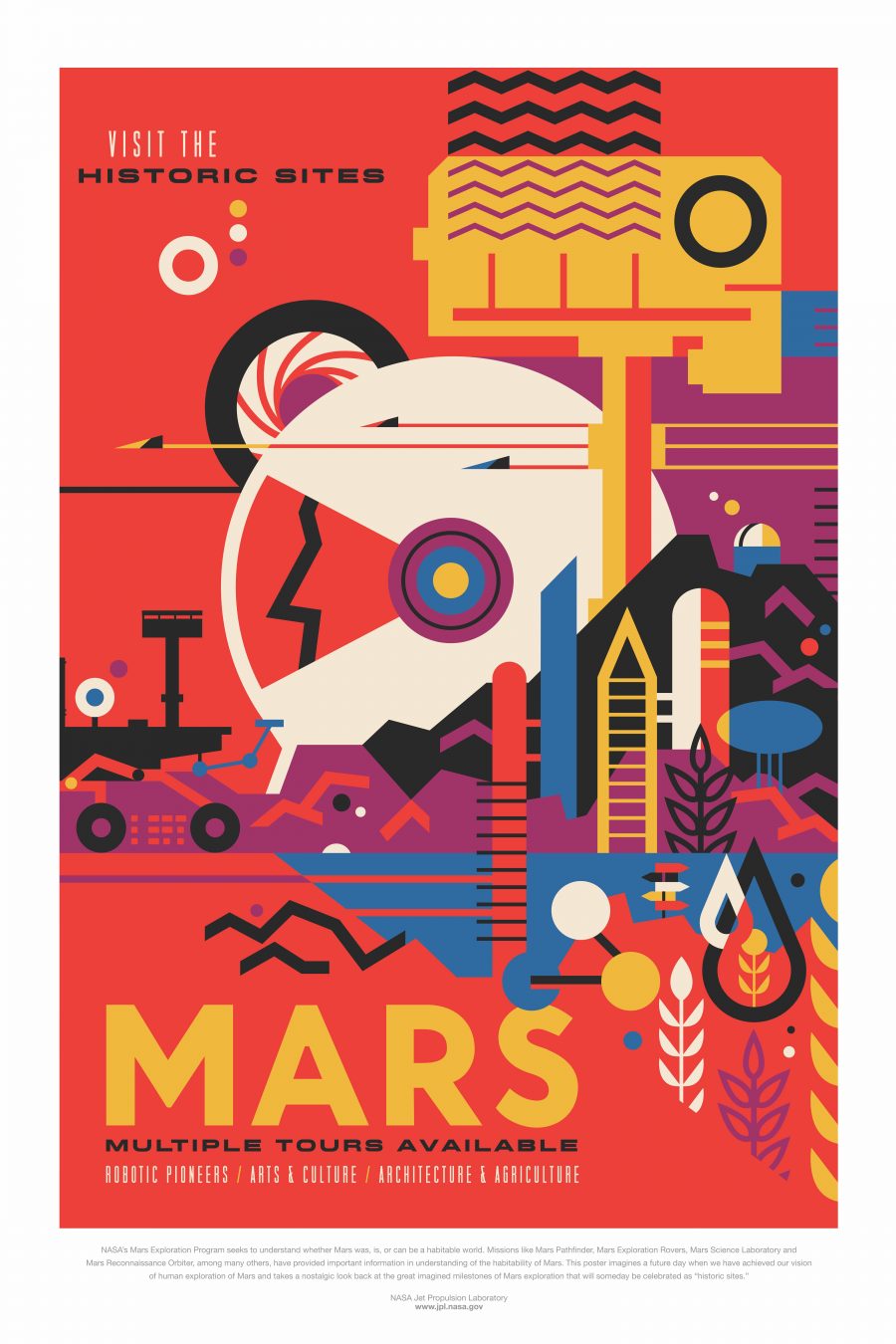

More recently, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory has enlisted a team of nine artists, designers, and illustrators to collaborate on 14 posters, a visual throwback to the ones the WPA created between 1938 and 1941 to spark public interest in the National Parks. You can see the results at the Exoplanet Travel Bureau.

View an album of 25 historic works from NASA’s Art Program here.

Related Content:

Star Trek‘s Nichelle Nichols Creates a Short Film for NASA to Recruit New Astronauts (1977)

NASA Digitizes 20,000 Hours of Audio from the Historic Apollo 11 Mission: Stream Them Free Online

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Join her in NYC on Monday, September 9 for another season of her book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

NASA Enlists Andy Warhol, Annie Leibovitz, Norman Rockwell & 350 Other Artists to Visually Document America’s Space Program is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2YVZvcT

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment