Discover Emily Dickinson’s Herbarium: A Beautiful Digital Edition of the Poet’s Collection of Pressed Plants & Flowers Is Now Online

So many writers have been gardeners and have written about gardens that it might be easier to make a list of those who didn’t. But even in this crowded company, Emily Dickinson stands out. She not only attended the fragile beauty of flowers with an artist’s eye—before she’d written any of her famous verse—but she did so with the keen eye of a botanist, a field open at the time to anyone with the leisure, curiosity, and creativity to undertake it.

“In an era when the scientific establishment barred and bolted its gates to women,” Brain Pickings’ Maria Popova writes, “botany allowed Victorian women to enter science through the permissible backdoor of art.”

In Dickinson’s case, this involved the pressing of plants and flowers in an herbarium, preserving their beauty, and in some measure, their color for over 150 years. The Harvard Gazette describes this very fragile book, made available in 2006 in a full-color digital facsimile on the Harvard Library site:

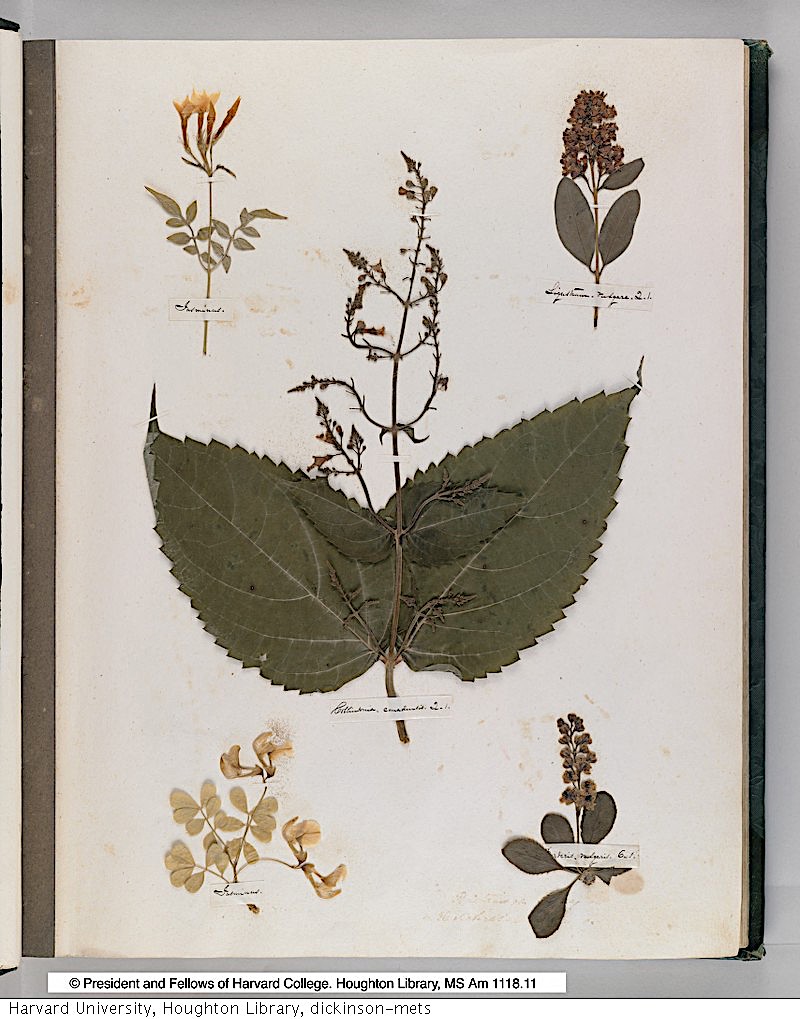

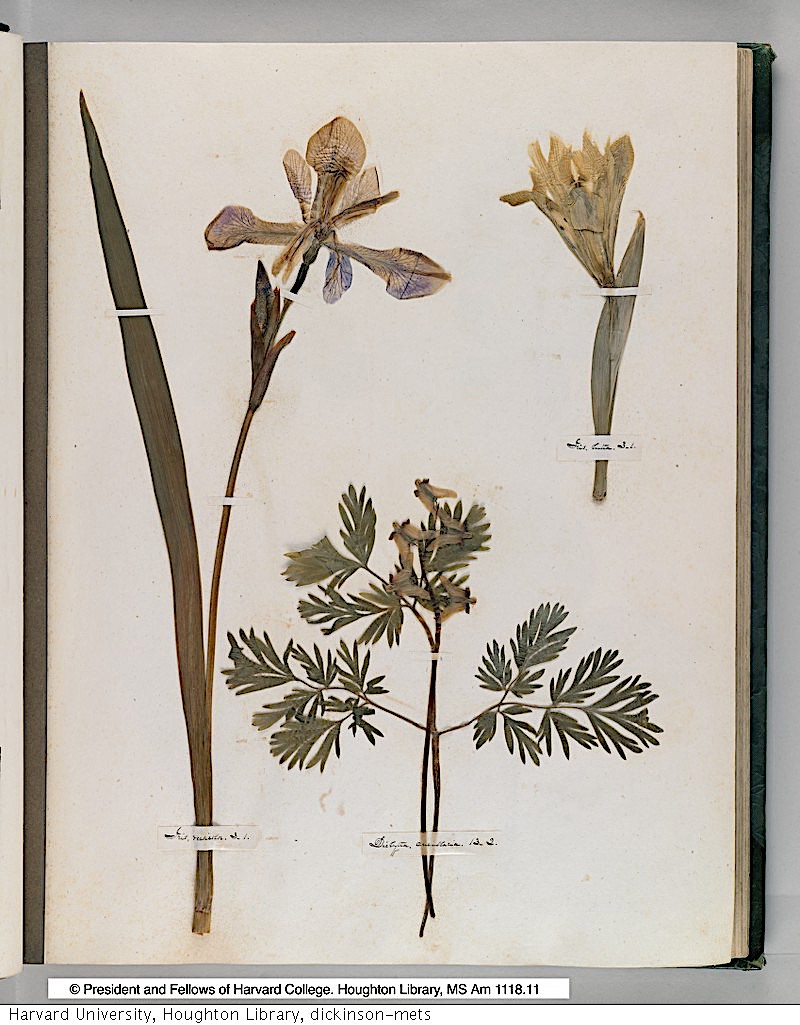

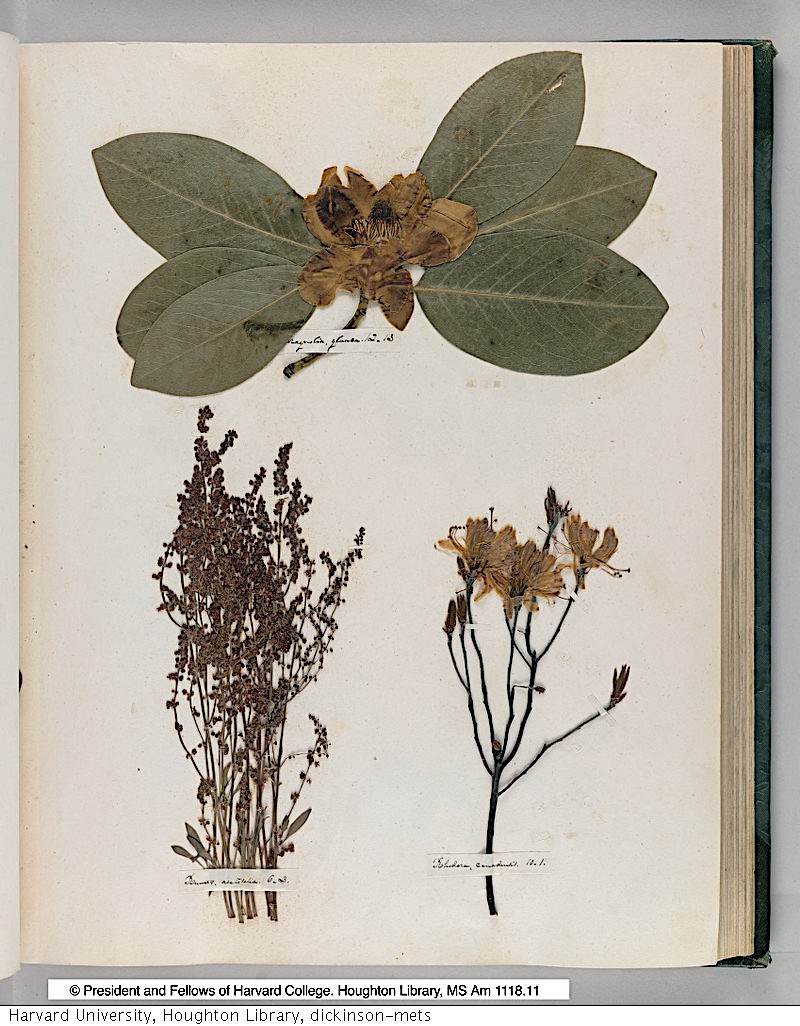

Assembled in a patterned green album bought from the Springfield stationer G. & C. Merriam, the herbarium contains 424 specimens arranged on 66 leaves and delicately attached with small strips of paper. The specimens are either native plants, plants naturalized to Western Massachusetts, where Dickinson lived, or houseplants. Every page is accompanied by a transcription of Dickinson’s neat handwritten labels, which identifies each plant by its scientific name.

The book is thought to have been finished by the time she was 14 years old. Long part of Harvard’s Houghton Library collection, it has also long been treated as too fragile for anyone to view. The only access has come in the form of grainy, black and white photographs. For the past few years, however, scholars and lovers of Dickinson’s work have been able to see the herbarium in these stunning reproductions.

The pages are so formally composed they look like paintings from a distance. Though mostly unknown as a poet in her life, Dickinson was locally renowned in Amherst as a gardener and “expert plant identifier,” notes Sara C. Ditsworth. The herbarium may or may not offer a window of insight into Dickinson’s literary mind. Houghton Library curator Leslie A. Morris, who wrote the forward to the facsimile edition, seems skeptical. “I think that you could read a lot into the herbarium if you wanted to,” she says, “but you have no way of knowing.”

And yet we do. It may be impossible to separate Dickinson the gardener and botanist from Dickinson the poet and writer. As Ditsworth points out, “according to Judith Farr, author of The Gardens of Emily Dickinson, one-third of Dickinson’s poems and half of her letters mention flowers. She refers to plants almost 600 times,” including 350 references to flowers. Both her herbarium and her poetry can be situated within the 19th century “language of flowers,” a sentimental genre that Dickinson made her own, with her elliptical entwining of passion and secrecy.

The first two specimens in Dickinson’s herbarium are the jasmine and the privet: “You have jasmine for poetry and passion” in the language of flowers, Morris points out, “and privet,” a hedge plant, “for privacy.” There is no need to see this arrangement as a prediction of the future from the teenage botanist Dickinson. Did she plan from adolescence to become a recluse poet in later life? Perhaps not. But we can certainly “read into” the language of her herbarium some of the same great themes that recur over and over in her work, carried across by images of plants and flowers. See Dickinson’s complete herbarium at Harvard Library’s digital collections here, or purchase a (very expensive) facsimile edition of the book here.

Related Content:

The Online Emily Dickinson Archive Makes Thousands of the Poet’s Manuscripts Freely Available

How Emily Dickinson Writes A Poem: A Short Video Introduction

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Discover Emily Dickinson’s Herbarium: A Beautiful Digital Edition of the Poet’s Collection of Pressed Plants & Flowers Is Now Online is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2YsP1WP

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment