Almost immediately after Scottish doctor Edward Jenner learned how to inoculate humans against smallpox in 1796, mass movements sprang up in England and the U.S. to oppose the measure. The rejection of inoculation and vaccination generally made its stand on “political grounds,” says Yale historian Frank Snowden. For over two hundred years, people have “widely considered [vaccines to be] another form of tyranny.” In the 19th century, fears of government control mutated into pseudoscientific conspiracy theories claiming the smallpox vaccine might cause, for example, the growth of hooves and horns or the birth of human/cow hybrid babies.

The pushback against the smallpox vaccine, writes Slate’s Nick Keppler, occurred during a time “when arguments about bodily integrity and religious objection carried as much weight as scientific evidence.” But vaccine science progressed nonetheless, and scientific institutions – very much in league with government by the mid-20th century – shared their largesse in the form of medical breakthroughs and consumer conveniences. “The postwar era was a very trust-in-science-era,” says researcher scientist Jonathan M. Berman, author of Anti-Vaxxers: How to Challenge a Misinformed Movement. “The public not just accepted, but cheered, the headline-making work of guys in white lab coats,” Keppler remarks.

Not everyone was cheering for Jonas Salk, the March of Dimes, and the polio vaccine, however. While celebrities like Elvis Presley legitimized the vaccine in the eyes of a previously skeptical public, a few fervent anti-vaxxers rose to prominence, some using the same combination of fear mongering, pseudoscientific speculation, and conspiratorial thinking common to the smallpox era – and common, once again, in the time of COVID-19.

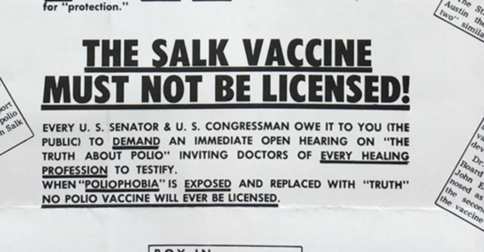

One of these figures, Florida businessman Duon Miller, founded a cosmetics company, then invested his own money and that of others into an organization called Polio Prevention Inc., a one-man operation that purported to fight polio with information about nutrition. Miller’s organization actually served to undermine the vaccine with a host of outrageous, logically fallacious claims about the causes of polio and the dangers of vaccination. As Keppler notes:

Like today’s COVID skeptics, Miller cherry-picked physicians who were skeptical of polio as a virus and misrepresented facts. One mailer was a rapid fire of out-of-context information: Salk “isn’t entirely satisfied with the vaccine.” Some children still got polio after being vaccinated. And just as the “real” number of COVID-19 deaths pales in comparison to vaccine deaths in some dark corners of the internet, so it was with polio in Miller’s world: “Polio ‘CRIPPLES’ and Polio ‘DEATHS’ are merely ‘Statistics’ to the ‘Charity-Brokers,’ whose record to date of ‘Cripples’ and ‘Deaths’ is TRULY DISGRACEFUL.”

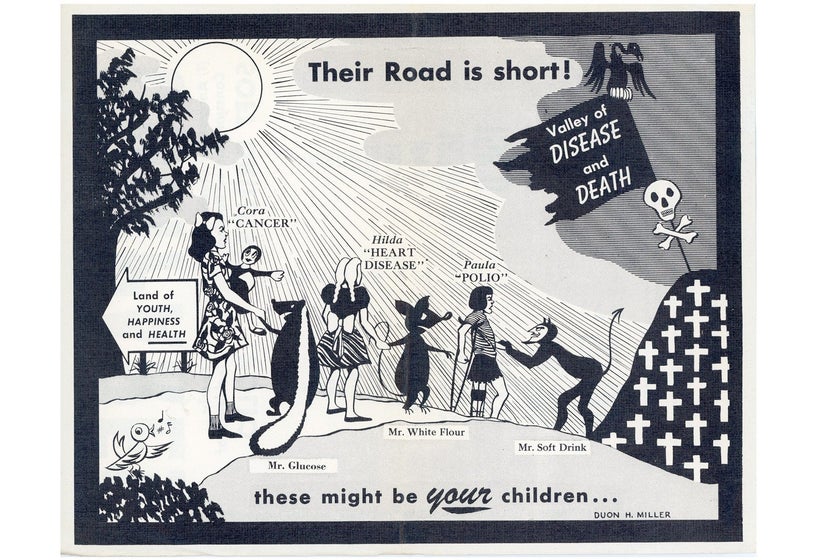

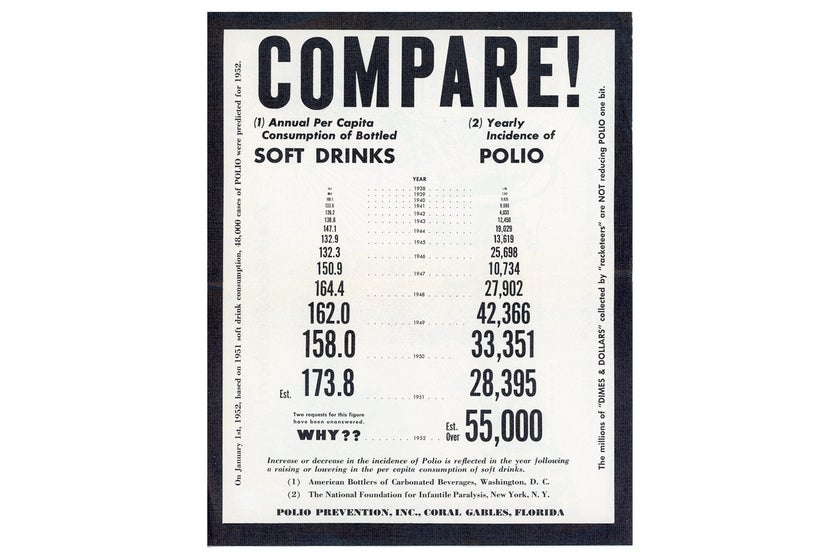

Like many conspiracy theorists today, Miller’s claims contained several kernels of truth, misplaced in the service of a bizarre crusade. Research now ties excess consumption of soft drinks, white flour, and refined sugar to an increase in cancers and heart disease. In this, Miller was prescient, given that these are the some of the biggest killers in the country. But this had nothing to do with the polio virus. Miller’s uncritical thinking, mistaking large-scale correlations for causation, typifies conspiracy theories. His appeal to the welfare of children also strikes a familiar chord, but it’s unsurprising in this case, given that “polio was a disease of children,” says René F. Najera, editor of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia’s History of Vaccines project, “so people were already afraid for their children.” Comparatively, COVID-19 “has largely left children alone … so we don’t mobilize as much.”

Keppler draws many other parallels between Miller’s personal anti-polio vaccine project and the efforts today to resist the COVID-19 vaccine, all representative of American anti-intellectualism and the well-funded will to disbelieve what the science clearly demonstrates. Miller distributed mailers in schools around Florida, accepted hundreds in donations, and printed thousands of pamphlets for distribution. He even offered to get injected with the polio virus to show that it was harmless. However, “federal charges ended Miller’s crusade,” when he was charged with “sending ‘libellous, scurrilous and defamatory’ statements through the mail” in 1954, the year Salk readied nationwide trials of the vaccine. Five years later, “U.S. polio cases were about 14 percent of what they were in 1952, thanks to vaccination,” not, as Miller would have the public believe, a change in diet. “Give us proper diets,” he continued to write to newspapers, “and we’ll solve the physical imperfections of Americans young and old.” He might have been on to a good argument about nutrition just by chance, but the public had no reason to listen to his opinions about polio simply because he could afford to circulate them.

via Steve Silberman

Related Content:

How Do Vaccines (Including the COVID-19 Vaccines) Work?: Watch Animated Introductions

Dying in the Name of Vaccine Freedom

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

from Open Culture https://www.openculture.com/2022/02/the-anti-vaxxer-who-waged-war-against-jonas-salk-his-polio-vaccine-when-history-keeps-repeating.html

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment