In 1922, a Novelist Predicts What the World Will Look Like in 2022: Wireless Telephones, 8-Hour Flights to Europe & More

A century ago, the popular English novelist W.L. George sat down and put his mind to envisioning the world we live in today. That world has not, alas, turned out to be one in which his books are much read, but in his day a great many readers were moved by his social cause-driven fiction and reportage. One might compare him to Upton Sinclair, his contemporary on the other side of the Atlantic. In the Paris-born-and-raised George’s ancestral homeland, George Orwell described him as an author of what G.K. Chesterton called “good bad books,” singling out for praise his 1920 novel Caliban amid the “shoddy rubbish” of his wider oeuvre.

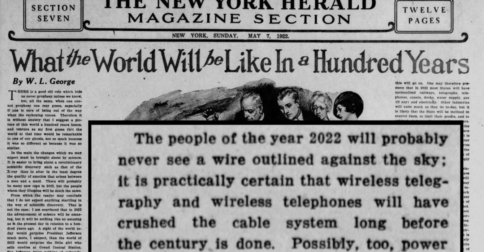

Still even authors of rubbish — and perhaps especially authors of rubbish — can sense the shape of things to come. For its edition of May 7, 1922, the New York Herald commissioned George to share that sense with their readers. In response he described a world in which “commercial flying will have become entirely commonplace,” reducing the separation of America and Europe to eight hours, and whose passenger steamers and railroads will have consequently fallen into obsolescence. “Wireless telegraphy and wireless telephones will have crushed the cable system,” resulting in generations who’ll never have seen “a wire outlined against the sky.”

That goes for the transmission of electricity as well, since George credits (a bit hastily, it seems) the possibility of wireless power systems of the kind researched by Nikola Tesla. In 2022, coal will take a distant backseat to the tides, the sun, and radium, and “it may also be that atomic energy will be harnessed.” As for the cinema, “the figures on the screen will not only move, but they will have their natural colors and speak with ordinary voices. Thus, the stage as we know it to-day may entirely disappear, which does not mean the doom of art, since the movie actress of 2022 will not only need to know how to smile but also how to talk.”

Other women, however, have proven just as capable as George had imagined: “All positions will be open to them and a great many women will have risen high. The year 2022 will probably see a large number of women in Congress, a great many on the judicial bench, many in civil service posts, and perhaps some in the President’s Cabinet.” Georges foresees the birth-control pill, but also the “pill lunch.” Unlike some reformers, he hesitates to declare the abolition of the family, but he does imagine the “majority of mankind” occupying modular homes in high-rise communal dwellings (“I have a vision of walls, furniture, and hangings made of more or less compressed papier-mâché”), all gathered in climate-controlled cities set under glass.

On the whole, in 2022, “the advancement of science will be amazing, but it will be nothing like so amazing as is the present day in relation to a hundred years ago.” Indeed, he suspects that a glimpse of our reality wouldn’t much surprise “the little girl who sells candies at Grand Central Station.” It could even be dull, what with complete settlement and development leaving “no more opportunity in America than there is in England to-day.” In 1922, George could write that “in fiction, America leads the world by sincerity, faith and fearlessness,” and believe that “in 2022 American literature will be a literature of culture. The battle will be over and the muzzle off. There will be no more things one can’t say, and things one can’t think.” Whatever the inspirations of his prophecy, they must not have told him about social media.

Related content:

In 1900, Ladies’ Home Journal Publishes 28 Predictions for the Year 2000

In 1926, Nikola Tesla Predicts the World of 2026

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

from Open Culture https://www.openculture.com/2022/02/in-1922-a-novelist-predicts-what-the-world-will-look-like-in-2022.html

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment