In the second decade of the 20th century, American editor Margaret C. Anderson published The Little Review, a monthly literary journal of modernist and experimental prose, poetry, and art. Four years into its existence, at the beginning of 1918, Anderson announced to her readers this:

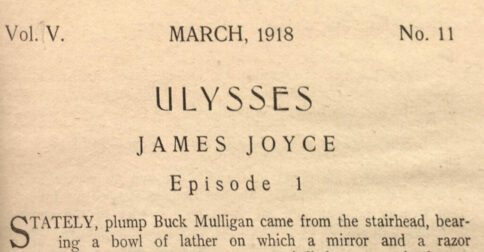

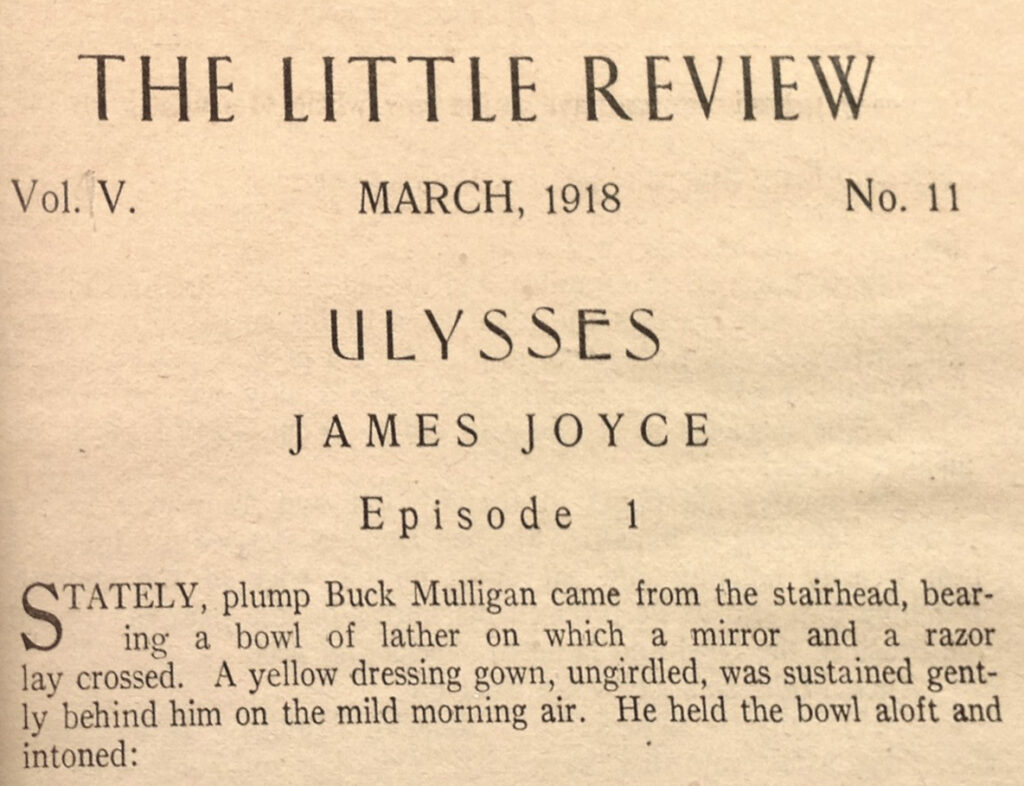

“I have just received the first three instalments [sic] of James Joyce’s new novel which is to run serially in The Little Review, beginning with the March number.

It is called “Ulysses”.

It carries on the story of Stephen Dedalus, the central figure in ‘A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man”.

It is, I believe, even better than the “Portrait”.

So far it has been read by only one critic of international reputation. He says: “It is certainly worth running a magazine if one can get stuff like this to put in it. Compression, intensity. It looks to me rather better than Flaubert”.

This announcement means that we are about to publish a prose masterpiece.”

February 2, 2022 marked the 100th anniversary of Ulysses, the day on which the full novel, first serialized in The Little Review, was published. Joyce, like many of The Little Review’s British and European writers, came to Anderson through her fellow editor Ezra Pound. Anderson might have sensed the greatness that was to come and she knew the danger in that greatness. In the end, publishing Ulysses would make her an enemy of the state.

Over at the Modernist Journals Project, you can read every single issue of The Little Review (and other such magazines) to place this revolutionary novel in context. The March 1918 issue which begins the journey of Dedalus and Leopold Bloom also features works by Wyndham Lewis and Ezra Pound, Ford Madox Ford, Jessica Dismorr, and Arthur Symons; letters (and some hate mail) from readers; advertisements for other literary magazines like The Quill, The Pagan, and The Egoist; ads for restaurants in Greenwich Village, and one for the Berlitz School of Languages; and a final appeal for more readers.

The most interesting of these sections is Pound’s screed against American obscenity laws. The Little Review had already had an issue confiscated by the US Post Office. In 1917, a Wyndham Lewis story about a soldier who gets a girl pregnant and abandons her was declared obscene, both for “lewdness” and its anti-war stance. Pound suspected the government was targeting Anderson and her co-editor (and lover) Jane Heap for their support of anarchists Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, along with their anti-war stances.

The Wyndham Lewis incident had made it difficult for Anderson and Heap to find a publisher, so they knew some of the risks in beginning the serial. Soon enough they ran into trouble. Ulysses consists of 18 chapters or “Episodes”. The US government seized the issues featuring Episode 8 (“Lestrygonians”), Episode 9 (“Scylla and Charybdis”), and Episode 12 (“Cyclops”) and burned them. But it was Episode 13, “Nausicaa,” that led to charges being filed against the publishers. The chapter, which features a girl exposing herself and Leopold Bloom masturbating to orgasm (but written in such a, well, Joycean way that most would just miss it), was too much for some.

The trial that followed was a travesty, including a judge ruling that the offensive sections of “Nausicaa” not be read out loud because a woman was present. When it was pointed out that the woman was the publisher Anderson herself, he declared “she didn’t know the significance of what she was publishing”. Anderson and Heap were found guilty, forced to discontinue publishing “Ulysses” and fined one hundred dollars.

The Little Review printed a section of Episode 14 (“Oxen of the Sun”) and then stopped. Anderson thought of giving up the magazine, but turned over control to Heap. The magazine continued publishing until 1929, but removed their motto: “Making No Compromise with the Public Taste.”

James Joyce did not stop, however, and Sylvia Beach—an ex-pat living in Paris and running the bookstore Shakespeare and Co.—published the full novel in 1922. Americans would have to wait one more year, 1923, to read this “obscene” novel.

Anderson was correct however—-she had a major role in promoting this “prose masterpiece.” And one hundred years later, Puritanical Americans are still banning and burning books, which is only resulting, like it did for Joyce’s novel, in sending the works into the Best Seller lists.

Related content:

James Joyce’s Ulysses: Download as a Free Audio Book & Free eBook

Virginia Woolf on James Joyce’s Ulysses, “Never Did Any Book So Bore Me.” Shen Then Quit at Page 200

James Joyce’s Crayon Covered Manuscript Pages for Ulysses and Finnegans Wake

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the Notes from the Shed podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, and/or watch his films here.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3glK6b9

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment