Four years ago, when the world commemorated the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death, some marked the event with reference to a dramatic work hardly anyone’s ever read, and fewer have ever seen performed. Called The Booke of Sir Thomas More, “this late 16th or early 17th-century play,” the British Library notes, “is not always included among the Shakespearean canon, and it was not until the 1800s that it was even associated with the Bard of Avon.”

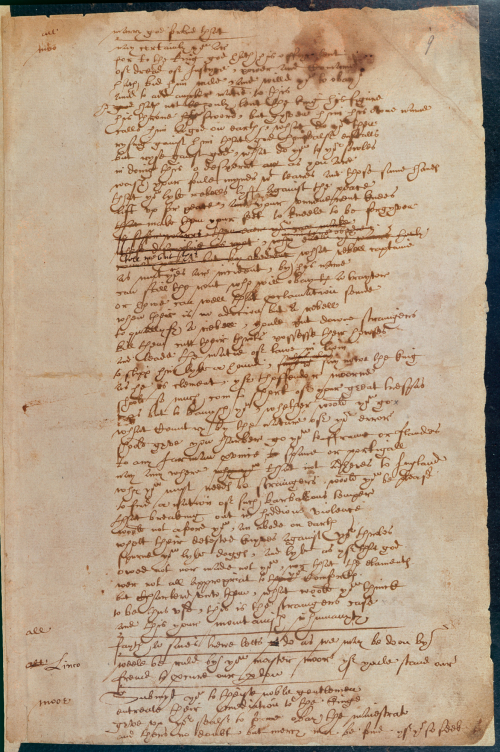

Since then, Sir Thomas More has become famous, at least among literary scholars, as the only surviving example of Shakespeare’s handwriting next to his will. It also became briefly internet famous in 2016 when Sir Ian McKellen reprised the title role he first played in 1964 for a dramatic reading in London that spoke eloquently, centuries later, to the moment. The play itself is the work of several dramatists, and the original text, from sometime between 1590 and 1605, is a patchwork of pages of insertions and six different scribal hands, Shakespeare’s very likely among them.

That same year, the British Library put a scan of the Shakespeare-penned pages of the play online and put the physical manuscript on display in an exhibit called Shakespeare in Ten Acts. Now, they have uploaded the full, scanned manuscript to their Digitized Manuscripts page and you can view it here. “In these pages we can perhaps see the master playwright at work, musing, composing and correcting his text: a window into Shakespeare's dramatic art, as it were.” We can hear what McKellen calls the “human empathy” in a speech “symbolic and wonderful… so much at the heart of Shakespeare’s humanity.”

The speech, which McKellen discusses above, has the humanist More passionately addressing a mob who are attempting to violently deport French protestant refugees. More did indeed address a rioting mob on May 1, 1517, what came to be known as “Evil May Day” (he was later executed in 1535 for treason when he refused to back Henry VIII against the Catholic Church). The play, which shows his actions as especially heroic, was censored by Edwin Tilney, Master of the Revels, and never performed until McKellen took the role. (He has joked that he may be “the last actor who can say ‘I created a part written by William Shakespeare.’”)

Read a transcription of the full, 147-line More speech thought to be by Shakespeare, and written in his own hand, at Quartz. “Proving that More’s words were indeed written by Shakespeare is not straightforward,” the British Library notes, though scholars have generally agreed on the authorship since the late 19th century, based on evidence you can read about here. But "in their keen sympathy for the plight of the alienated and dispossessed," these lines "seem to prefigure the insights of great dramas of race such as The Merchant of Venice and Othello.”

One can see, given Shakespeare's sympathy for social outsiders, why he would be drawn to More's speech, or why he might have been handpicked among other dramatists at the time to write the philosopher’s broad-minded plea for tolerance. See the full manuscript of The Booke of Sir Thomas More here at the British Library's Digitized Manuscripts.

Related Content:

Ian McKellen Reads a Passionate Speech by William Shakespeare, Written in Defense of Immigrants

What Shakespeare’s Handwriting Looked Like

What Shakespeare Sounded Like to Shakespeare: Reconstructing the Bard’s Original Pronunciation

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

The Only Surviving Script Written by Shakespeare Is Now Online is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/32eLj3M

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment