Some firemen today may complain about the boredom of all the time spent doing nothing at the station between calls, but when the hour comes to do battle with a serious blaze, no one can say they have it easy. Firefighting has, of course, never been a particularly relaxed gig, especially back in the days before not just water cannon-equipped helicopters, and not just fire engines, but fire hoses as we know them today. Putting out urban conflagrations without much water at hand is one thing, but imagine having to do it every day in a densely packed, highly flammable city like Tokyo — or rather Edo, as it was known between the early 17th and mid-19th centuries.

"Fires were frequent during this period because of crowded living conditions and wooden buildings, and the firefighters’ objective was to prevent a burning house from spreading its flames to the neighboring residences," writes Antique Trader's Kris Manty. With only weak water pumps at their disposal, Edo firemen "did not save the home, but rather tore down the burning structure and extinguished the fire. They did this by using long poles and other fire implements to demolish the blazing house and once the fire was doused, the surrounding homes were once again safe." In peacetime they "emerged as latter-day samurai heroes, with the motto, 'duty, sympathy and endurance'" — and bedecked in truly glorious handmade coats.

"Each firefighter in a given brigade was outfitted with a special reversible coat (hikeshi banten), plain but for the name of the brigade on one side and decorated with richly symbolic imagery on the other," says the Public Domain Review, where you can behold a gallery of such garments.

"These coats would be worn plain-side out and thoroughly soaked in water before the firefighters entered the scene of the blaze. No doubt the men wore them this way round to protect the dyed images from damage, but they were probably also concerned with protecting themselves, as they went about their dangerous work, through direct contact with the heroes and creatures represented on the insides of these beautiful garments."

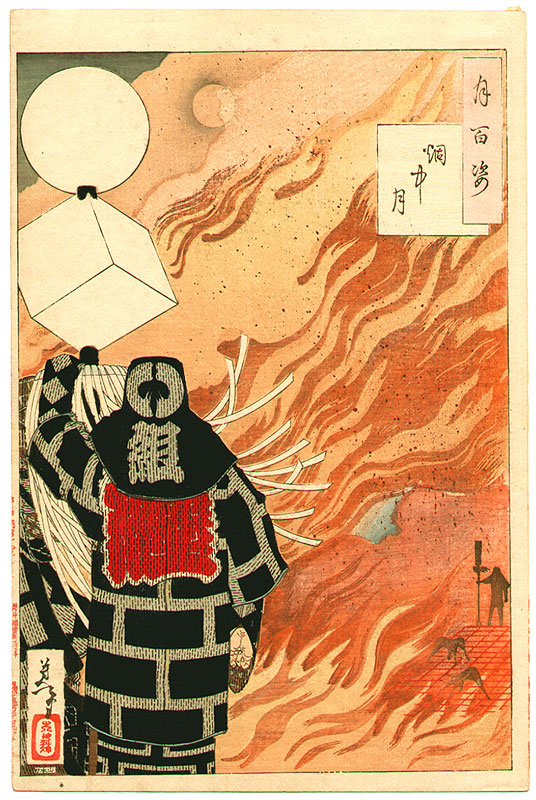

At the top of the post appears an example of an Edo fireman's coat held by the Philadelphia Museum of Art, one emblazoned with imagery from perhaps the best-known Japanese fable of all. "The center of this coat shows Momotaro, a legendary boy born from a peach, stomping on an ogre," says the museum's web site. "The smoke billowing behind him reminds us of the use of this coat, as does the fireman's hook pictured on the left sleeve. After their duty, firemen reversed their coats to display the bold and inspiring designs." As with many prominent figures of the age, Edo firefighters were also immortalized, coats and all, in ukiyo-e woodblock prints.

The noble image is not least thanks to the fact, writes Artelino's Dieter Wanczura, that "the great master Hiroshige I was the son of a fire warden in the service of the shogunate," and indeed a firefighter himself, keeping the job years into his printmaking career. The prints featured there include one depicting an 1805 clash "between sumo wrestlers and fire-fighters at Shinmei shrine," not an entirely unexpected occurrence given the rowdy public image of the kind of men who joined fire brigades. But "the average Japanese always cherished a liking for what they considered to be honorable bandits and outcasts" — and who today, anywhere in the world, could argue with their style?

Related Content:

Hand-Colored 1860s Photographs Reveal the Last Days of Samurai Japan

1850s Japan Comes to Life in 3D, Color Photos: See the Stereoscopic Photography of T. Enami

Female Samurai Warriors Immortalized in 19th Century Japanese Photos

Download Hundreds of 19th-Century Japanese Woodblock Prints by Masters of the Tradition

Hundreds of Wonderful Japanese Firework Designs from the Early-1900s: Digitized and Free to Download

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Behold 19th-Century Japanese Firemen’s Coats, Richly Decorated with Mythical Heroes & Symbols is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3jOJNM3

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment