The science of optics and the fine art of science illustration arose together in Europe, from the early black-and-white color wheel drawn by Isaac Newton in 1704 to the brilliantly hand-colored charts and diagrams of Goethe in 1810. Goethe’s illustrations are more renowned than Newton’s, but both inspired a considerable number of scientific artists in the 19th century. It would take a science writer, the French journalist and mathematician Amédée Guillemin, to fully grasp the potential of illustration as a means of conveying the mind-bending properties of light and color to the general public.

Guillemin published the hugely popular textbook Les phénomènes de la physique in 1868, eventually expanding it into a five-volume physics encyclopedia. (View and download a scanned copy at the Wellcome Collection.) He realized that in order to make abstract theories “comprehensible” to lay readers, Maria Popova writes at Brain Pickings, “he had to make their elegant abstract mathematics tangible and captivating for the eye. He had to make physics beautiful.” Guillemin commissioned artists to make 31 colored lithographs, 80 black-and-white plates, and 2,012 illustrated diagrams of the physical phenomena he described.

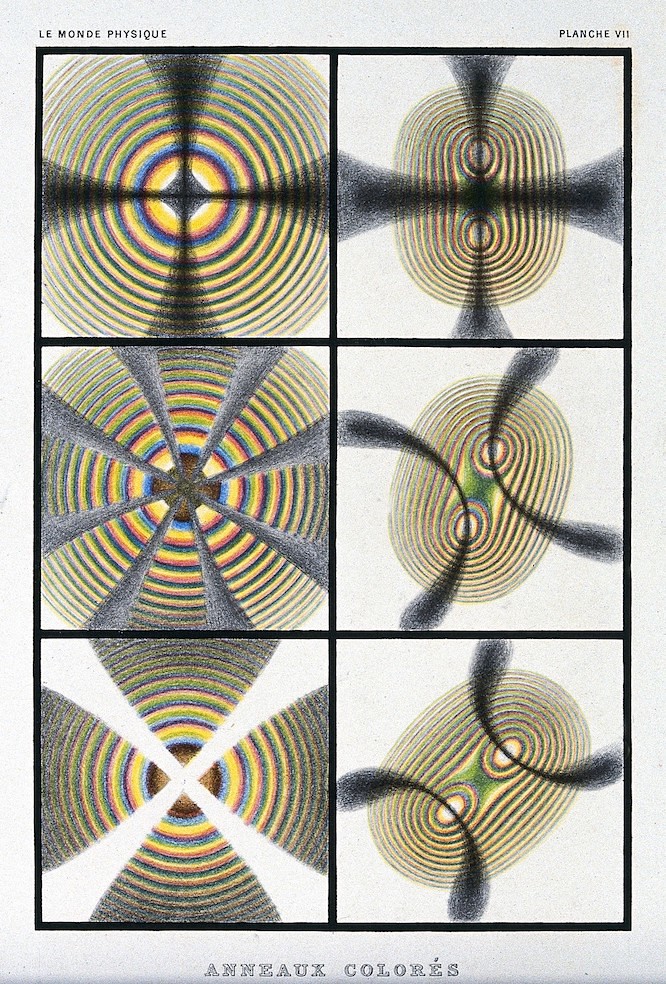

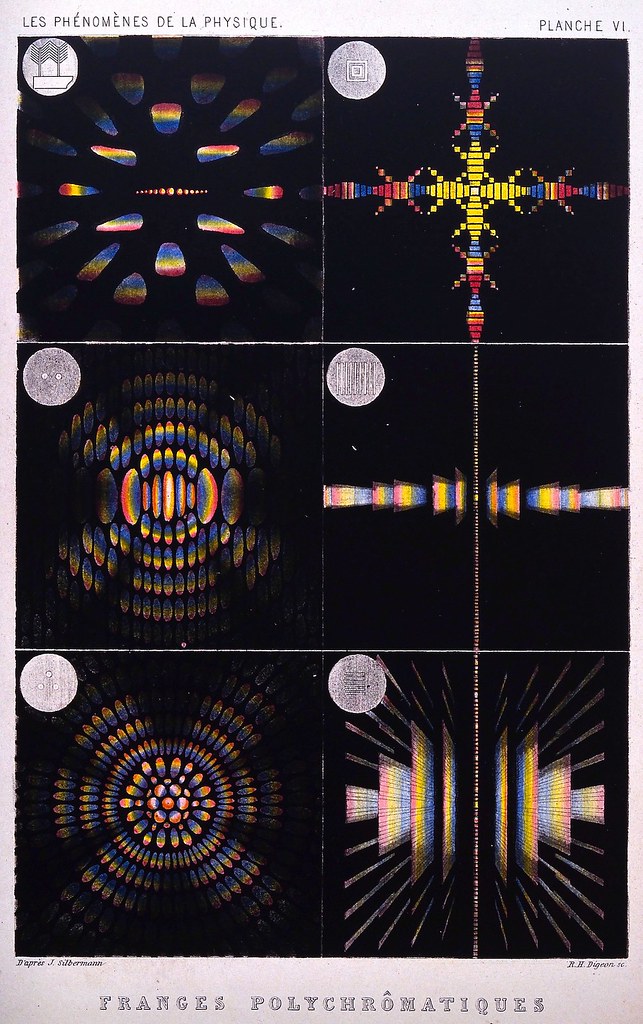

The most “psychedelic-looking illustrations,” notes the Public Domain Review, are by Parisian intaglio printer and engraver René Henri Digeon and “based on images made by the physicist J. Silbermann showing how light waves look when they pass through various objects, ranging from a bird’s feather to crystals mounted and turned in tourmaline tongs.”

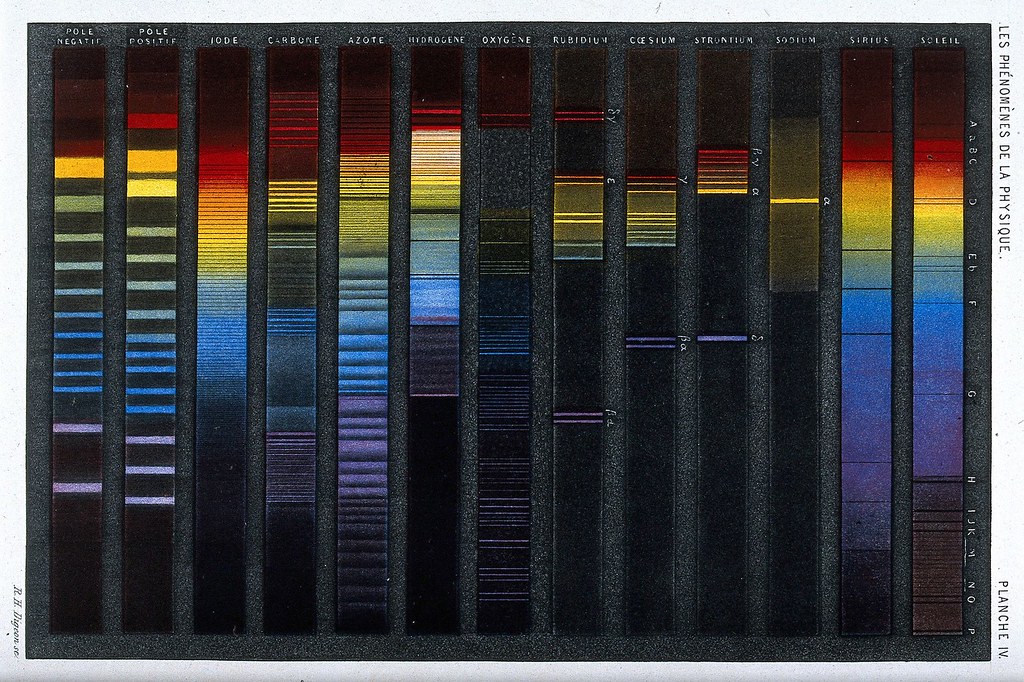

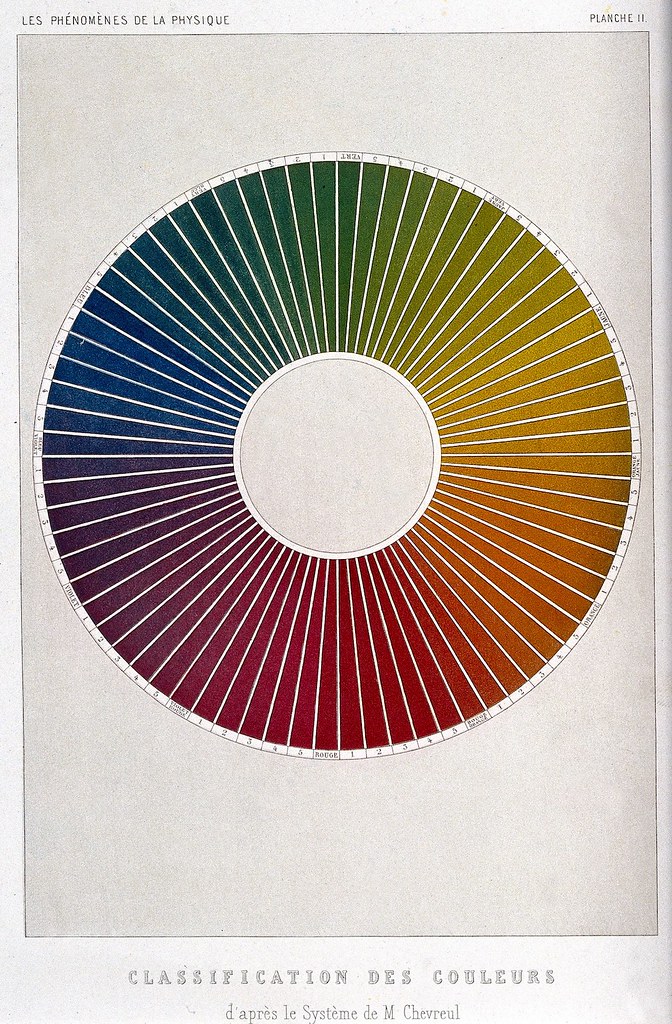

Digeon also illustrated the “spectra of various light sources, solar, stellar, metallic, gaseous, electric,” above, and created a color wheel, further down, based on a classification system of French chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul.

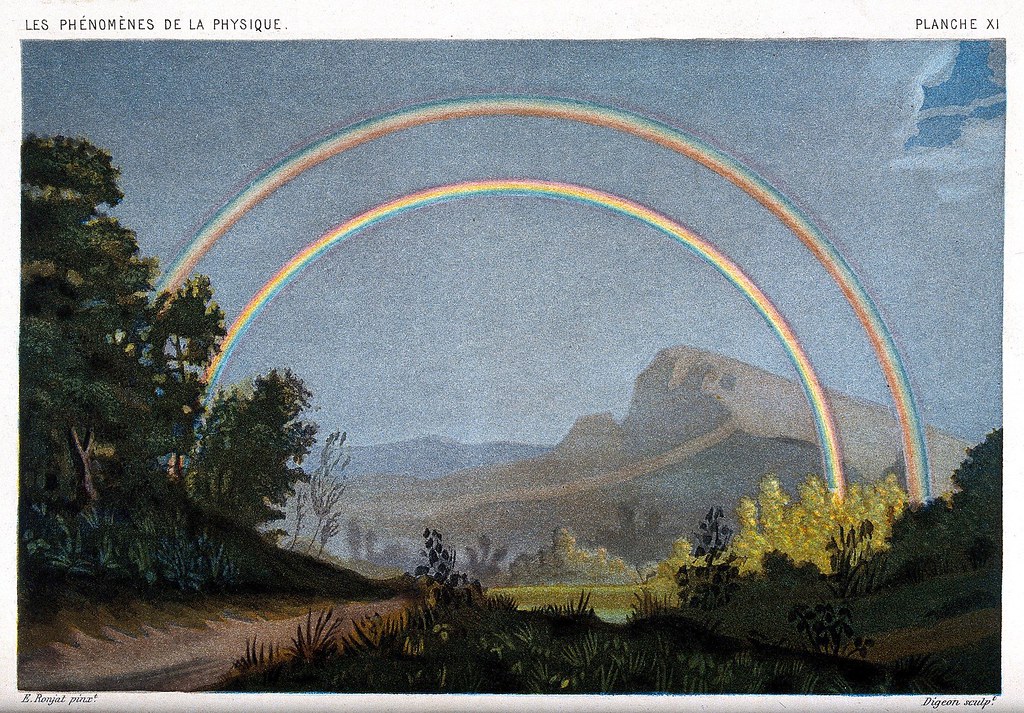

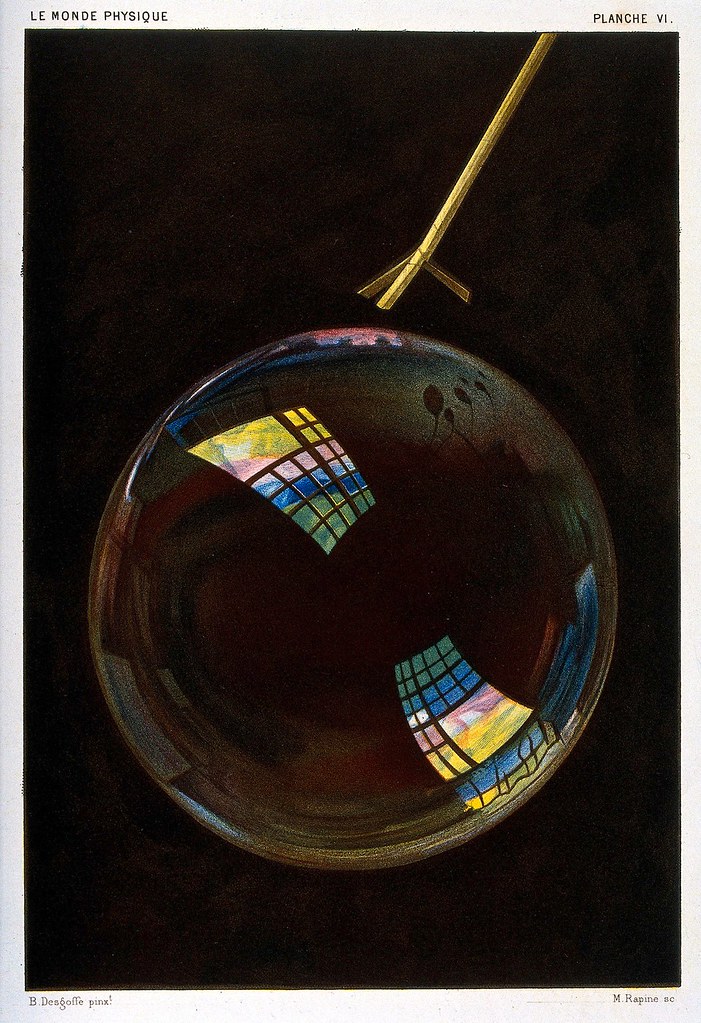

Many of Digeon’s images “were used to explain the phenomenon of birefringence, or double refraction,” the Public Domain Review writes (hence the double rainbow). In addition to his striking plates, this section of the book also includes the image of the soap bubble above, by artist M. Rapine, based on a painting by Alexandre-Blaise Desgoffe.

[The artists’] subjects were not chosen haphazardly. Newton was famously interested in the iridescence of soap bubbles. His observations of their refractive capacities helped him develop the undulatory theory of light. But he was no stranger to feathers either. In the Opticks (1704), he noted with wonder that, “by looking on the Sun through a Feather or black Ribband held close to the Eye, several Rain-bows will appear.”

In turn, Guillemin’s lavishly illustrated encyclopedia continues to influence scientific illustrations of light and color spectra. “In order thus to place itself in communion with Nature,” he wrote, “our intelligence draws from two springs, both bright and pure, and equally fruitful—Art and Science.” See more art from the book at Brain Pickings and the Public Domain Review.

Related Content:

The Vibrant Color Wheels Designed by Goethe, Newton & Other Theorists of Color (1665-1810)

A 900-Page Pre-Pantone Guide to Color from 1692: A Complete Digital Scan

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

The Phenomena of Physics Illustrated with Psychedelic Art in an Influential 19th-Century Textbook is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/34xWy4V

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment