The Japanese Fairy Tale Series: The Illustrated Books That Introduced Western Readers to Japanese Tales (1885-1922)

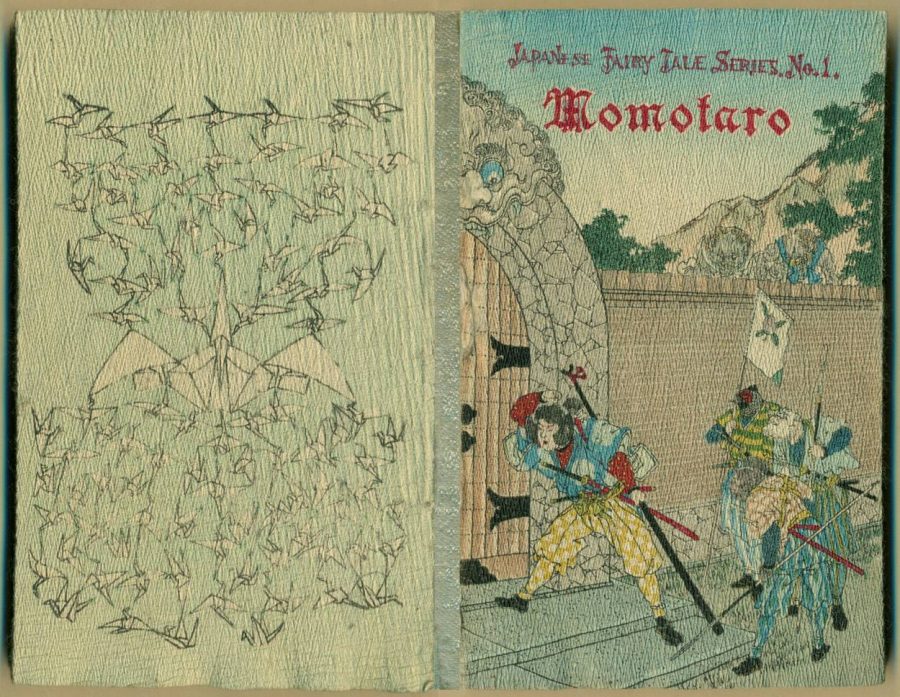

Everyone in Japan knows the story of Momotaro, the boy born from a peach who goes on to defeat the marauding ogres known as oni. The oldest known written versions of Momotaro's adventures date back to the 17th century, but even then the tale almost certainly had a long history of passage through oral tradition. And though Momotaro may well be the best-known Japanese folk hero, his story is just one in a body of folklore vast enough that few, even among avid enthusiasts, can claim to have mastered it in its entirety.

That vast body of Japanese folklore has provided no small amount of inspiration to comics, animation, and the other modern forms of storytelling that have brought many of these folktales to wider audiences — even global audiences, a project that began in the late 19th century.

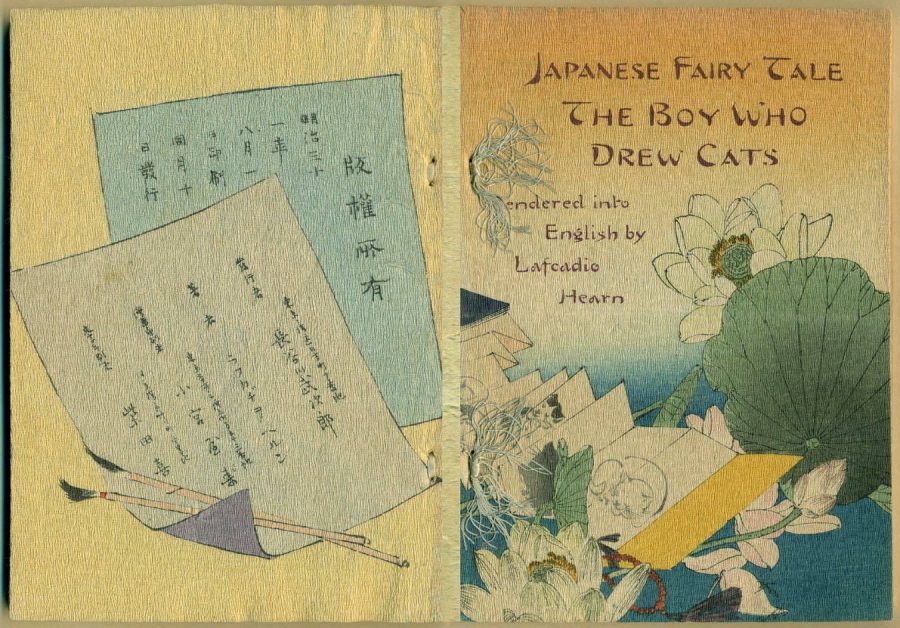

Their Western popularization has no greater figurehead than Lafcadio Hearn. A Greek-British writer who moved to Japan in 1890, Hearn later became a naturalized Japanese citizen and wrote such books as Japanese Fairy Tales, Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things, and The Boy Who Drew Cats.

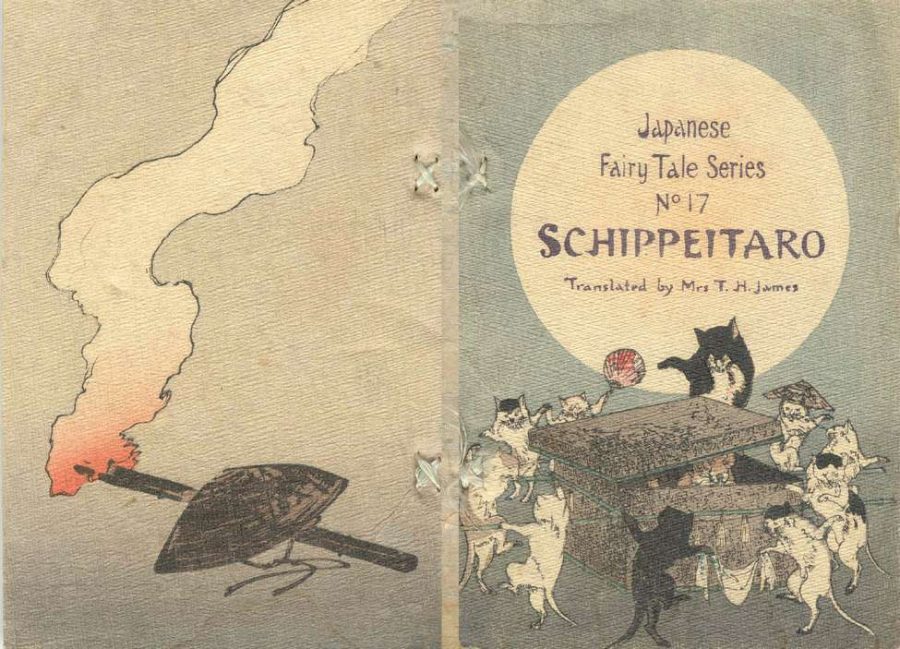

That last title, an English version of a Japanese folktale about a child who vanquishes a goblin rat in a monastery by drawing its natural enemies on the monastery walls, was also adapted in a series of beautifully illustrated crêpe-paper children's books put out by an enterprising Japanese publisher named Takejiro Hasegawa. "In twenty volumes, published between 1885 and 1922, the Fairy Tale series introduced traditional Japanese folk tales, first to readers of English and French, and later to readers of German, Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, and Russian," writes the Public Domain Review's Christopher DeCou.

Wanting to model the books on Japanese anthologies published in the sixteenth century, Hasegawa hired traditional Japanese woodblock printers like Kobyashi Eitaku, Suzuki Kason, and Chikanobu to illustrate them. And, for the translation work, he drew on the local missionary community to which his own English education had put him in contact. "The earliest volumes in the Japanese Fairy Tale Series really were very much a product of Tokyo’s close-knit expat community," DeCou writes. A growing Western interest in Japonisme, as well as "Hasewaga’s wheeling and dealing at World’s Fairs" and the good sense to bring the famous Hearn aboard the project, made the Japanese Fairy Tale Series into an enduring international success.

"At a time when publishing houses in London and New York dominated the market," DeCou writes, "Hasegawa’s press in Tokyo was producing equally beautiful volumes using traditional Japanese craftwork and broadcasting Japan’s culture to the world." You can see more pages of the Japanese Fairy Tale Books at the Public Domain Review, and complete digitizations at the site of book dealer George Baxley as well as at the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County and the Internet Archive. Like Hearn, Hasegawa understood that Japanese folklore had the appeal to cross temporal and cultural boundaries. But could even he have imagined that the very books in which he published them would still draw such fascination more than a century later?

Related Content:

Splendid Hand-Scroll Illustrations of The Tale of Genjii, The First Novel Ever Written (Circa 1120)

The First Museum Dedicated to Japanese Folklore Monsters Is Now Open

Enter a Digital Archive of 213,000+ Beautiful Japanese Woodblock Prints

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

The Japanese Fairy Tale Series: The Illustrated Books That Introduced Western Readers to Japanese Tales (1885-1922) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2nPvzSX

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment