John Milton’s Hand Annotated Copy of Shakespeare’s First Folio: A New Discovery by a Cambridge Scholar

Perhaps the most well-read writer on his time, English poet John Milton “knew the biblical languages, along with Homer’s Greek and Vergil’s Latin,” notes the NYPL. He likely had Dante’s Divine Comedy in mind when he wrote Paradise Lost. His own Protestant epic, if not a theological response to the Divine Comedy, had as much literary impact on the English language as Dante’s poem did on Italian. Milton would also have as much influence on English as Shakespeare, his near contemporary, who died eight years after the Paradise Lost author was born.

In some sense, English poet John Milton can be called a direct literary heir of Shakespeare, though he wrote in a different medium and idiom (almost a different language), and with a very different set of concerns.

Milton’s father was a trustee of the Blackfriar’s Theatre, where Shakespeare’s company of actors, the King’s Men, began performing in 1609, the year after Milton’s birth. And Milton’s first published poem appeared anonymously in the 1632 second folio of Shakespeare’s plays under the title “An Epitaph on the admirable Dramaticke Poet, W. Shakespeare.”

Now known as “On Shakespeare,” the poem laments the sorry state of Shakespeare’s legacy—his monument a “weak witness,” his work an “unvalued book.” It may be difficult to imagine a time when Shakespeare wasn’t revered, but his reputation only began to spread beyond the theater in the early 17th century. Milton’s poem was one of the first to proclaim Shakespeare’s greatness, as a poet who should lie “in such pomp” that “kings for such a tomb would wish to die.”

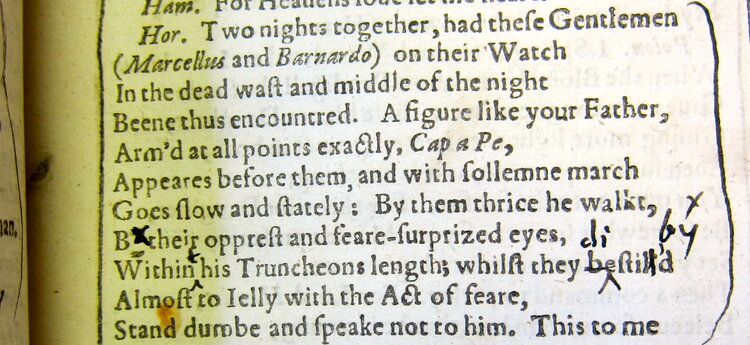

Now, it seems that significant further evidence of Milton’s admiration, and critical appreciation, of Shakespeare has emerged: in the form of Milton’s own, personal copy of the 1623 First Folio edition of Shakespeare's plays, with annotations in Milton’s own hand. Moreover, it seems this evidence has been sitting under scholar’s noses for decades, housed in the public Free Library of Philadelphia’s Rare Book Department, one of over 230 extant copies of the First Folio.

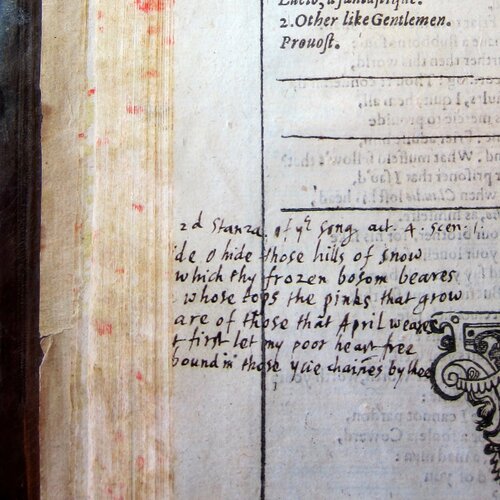

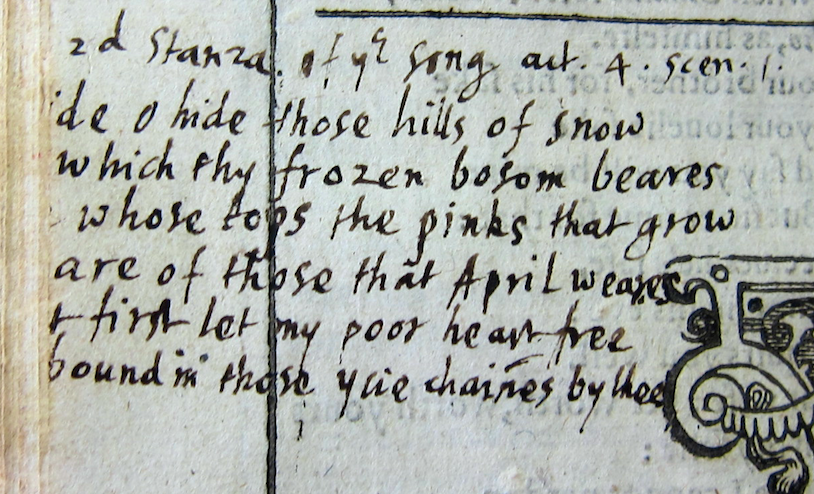

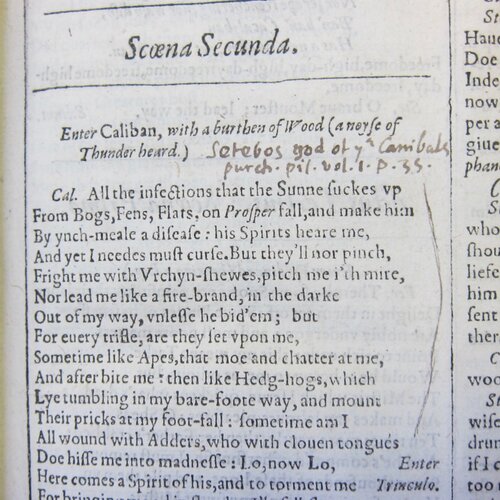

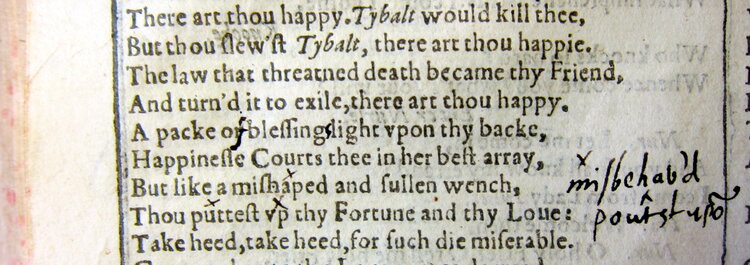

In a blog post at the Centre for Material Texts, the University of Cambridge’s Jason Scott-Warren makes his case that the annotated First Folio is Milton’s own, primarily, he writes, on the basis of paleography, or handwriting analysis. “This just looks like Milton’s hand,” he says, then walks through several comparisons with other known Milton manuscripts, such as his commonplace book and annotated Bible.

There is also the copious evidence for dating the book to the time Milton would have owned it, from the many marginal references to contemporary works like Samuel Purchas’ 1625 Pilgrimes and John Fletcher’s The Bloody Brother. Milton “added marginal markings to all of the plays except for Henry VI 1-3and Titus Andronicus,” notes Scott-Warren. His corrections—from the Quarto—emendations, and “smart cross-references” are “intelligent and assiduous.”

Anticipating blowback for his Milton theory, Scott-Warren asks, “wouldn’t his copy be bristling with cross-references, packed with smart observations and angrily censorious comments?” It would indeed, and “several distinguished Miltonists” have agreed with Scott-Warren’s analysis, many contacting him, he writes in a postscript, to say they’re “confident that this identification is correct." He adds that he has “been roundly rebuked for understating the significance of the discovery.”

This kind of self-reported validation isn’t exactly peer review, but we don’t have to take his word for it. Said scholars have made their approval publicly, enthusiastically, known on Twitter. And University of Pennsylvania Assistant Professor of English Claire M.L. Bourne has written a congratulatory essay on her blog. It was Bourne who spurred on Scott-Warren’s investigation with her own essay “Vide Supplementum: Early Modern Collation as Play-Reading in the First Folio,” published just months earlier this year.

Bourne was one of the first few scholars to thoroughly examine the Free Library of Philadelphia’s copy of the First Folio. But, she admits, she completely missed the Milton connection. “You can work for a decade,” she writes ruefully, “as I did, on a single book… and still be left with gaping holes in the narrative.” This new scholarship may not only have filled in the mystery of the book’s first owner and annotator; it may also show the full degree to which Milton engaged with Shakespeare, and give Milton scholars “a new and significant field of reference” for reading his work.

via MetaFilter

Related Content:

William Blake’s Hallucinatory Illustrations of John Milton’s Paradise Lost

Spenser and Milton (Free Course)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

John Milton’s Hand Annotated Copy of Shakespeare’s First Folio: A New Discovery by a Cambridge Scholar is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/32JdZPt

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment