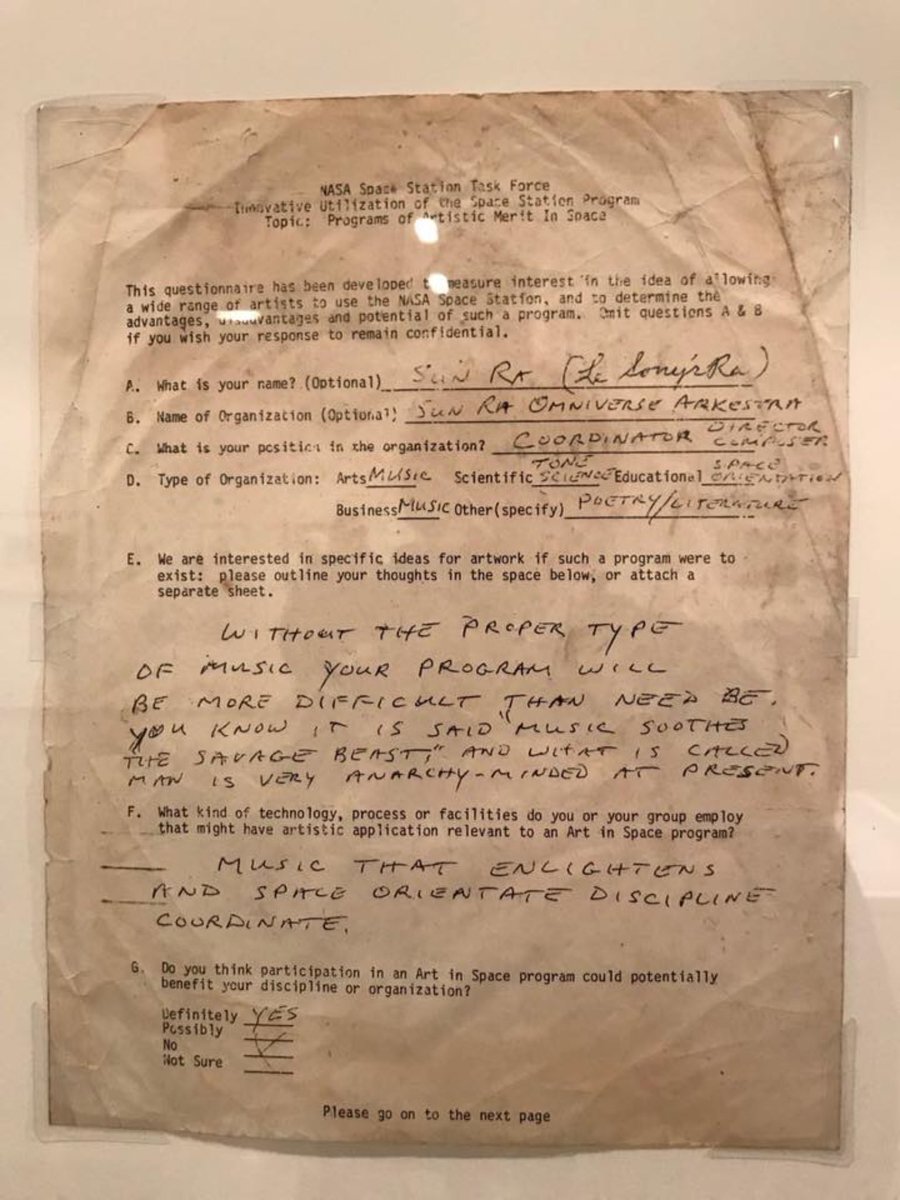

You may have seen the image above floating around, especially if you follow jazz lovers and writers like Ted Gioia: the first page of Sun Ra’s application to NASA’s art program. The program was “somewhat of a glorified PR campaign,” writes Shannon Gormley at Willamette Week, but one nonetheless that has employed many prominent artists since its inception in 1962, including Annie Leibovitz, Andy Warhol, Laurie Anderson, and Norman Rockwell. NASA has “enlisted musicians, poets and others for more variety,” the Administration notes. “Patti LaBelle even recorded a space-themed song.”

But Sun Ra—given name Herman Blount; legal name (as he writes in parentheses) Le Sony’r Ra—was not, it seems, considered when he applied in the 1960s, even if he more or less invented space jazz in the previous decade. After many years in Chicago, he’d relocated his free jazz big band, the Arkestra, to New York, where they influenced later Beats and the early psychedelic scene (just as he was to influence funk, prog, and fusion in the 70s, and come in for a major revival in the 90s through indie rock and hip hop.)

Likely, whoever read his application was unfamiliar with the creative idiosyncrasies of his language, written just as he sang and played—with incantatory repetition, syntactical surprises, and ALL CAPS all the time. The prodigious, visionary bandleader proposes to contribute “music that enlightens and space orientate discipline coordinate.” One might cast a wary eye on this description, from an applicant who lists their educational mission as “space orientation.” Unless you’d heard what Sun Ra meant by the phrase.

Take his orientation in 1961’s “Space Jazz Reverie” from The Futuristic Sounds of Sun Ra, recorded just after he arrived in New York, on the threshold of pushing the Arkestra further out into the solar system. The tune “ostensibly sounds like a large-ensemble take on hard bop,” writes Matthew Wuethrich at All About Jazz. "Mid-tempo swing, strange-but-not-unheard-of-intervals and a string of solos.” But the composition starts to warp and wobble. “Ra’s comping on the piano generates an unsettling backdrop.” A “bizarre bridge” after the solos throws things further off-kilter.

This is not cold, crystalline music of the stars, but an emotional journey into the excitation, coordination (to take his phrase), and defamiliarization of space travel. Listening to Sun Ra almost inclines me to believe his tales of interstellar travel and alien abduction—or at least to feel, for a few minutes, as though I had taken a cosmic trip. NASA’s art program would have certainly been enriched by his contributions, though whether it would have raised either one’s profile is uncertain.

Ra’s application “reads like a prophecy,” writes Gormley. We need music, in space and otherwise. “What is called man is very anarchy-minded at present,” he wrote. But Sun Ra himself was “anarchy-minded,” in the best sense of the term—he gave his imagination free rein and did not cater to any authority. This rankled many of his jazz peers, who frequently said he went too far. Sun Ra never seemed to bother about the criticism.

He may have taken the NASA snub a little hard. In his landmark 1972 film Space is the Place, he discusses the space program with a group of black Oakland youth, saying, “I see none of you have been invited.” Sun Ra and the young people to whom he brought the hope of outer space could not have known about the hidden history of African American scientists and astronauts in the space program. In any case, Ra had his own space program. A one-band cultural revolution that was too forward-looking for both jazz and NASA.

via Ted Gioia

Related Content:

Star Trek‘s Nichelle Nichols Creates a Short Film for NASA to Recruit New Astronauts (1977)

Sun Ra’s Full Lecture & Reading List From His 1971 UC Berkeley Course, “The Black Man in the Cosmos”

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Sun Ra Applies to NASA’s Art Program: When the Inventor of Space Jazz Applied to Make Space Art is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/305VwuC

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment